The Macintosh II was a popular computer in the era before Apple dominated the coffee shop user market, but for those of us still using our Mac II’s you may find that your SCSI hard drive isn’t performing the way that it should. Since this computer is somewhat of a relic and information on them is scarce, [TheKhakinator] posted his own hard drive repair procedure for these classic computers.

The root of the problem is that the Quantum SCSI hard drives that came with these computers use a rubber-style bump stop for the head, which becomes “gloopy” after some time. These computers are in the range of 28 years old, so “some time” is relative. The fix involves removing the magnets in the hard drive, which in [TheKhakinator]’s case was difficult because of an uncooperative screw, and removing the rubber bump stops. In this video, they were replaced with PVC, but [TheKhakinator] is open to suggestions if anyone knows of a better material choice.

This video is very informative and, if you’ve never seen the inside of a hard drive, is a pretty good instructional video about the internals. If you own one of these machines and are having the same problems, hopefully you can get your System 6 computer up and running now! Once you do, be sure to head over to the retro page and let us know how you did!

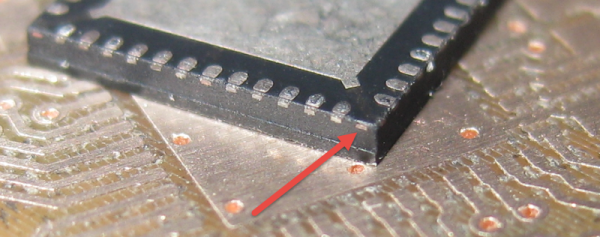

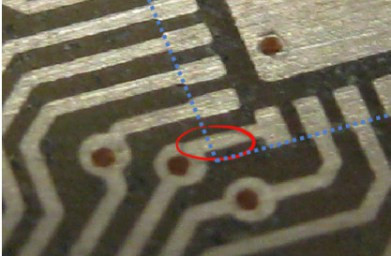

The PCB layout just happens to have a trace exiting right under this conductor. The two aren’t touching, but without solder mask, a bit of melted metal was able to mind the gap and connect the two conductors. [Eric] notes that although the non-pad isn’t documented, it’s easy to prove that it is connected to ground and was effectively pulling down the signal on that trace.

The PCB layout just happens to have a trace exiting right under this conductor. The two aren’t touching, but without solder mask, a bit of melted metal was able to mind the gap and connect the two conductors. [Eric] notes that although the non-pad isn’t documented, it’s easy to prove that it is connected to ground and was effectively pulling down the signal on that trace.

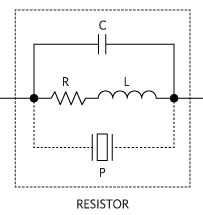

For resistors, you’ll also have to reckon with temperature dependence as well as the same range of piezoelectric and inductance characteristics that capacitors display. Worse, resistors can display variable resistance under higher voltages, and actually produce a small amount of random noise:

For resistors, you’ll also have to reckon with temperature dependence as well as the same range of piezoelectric and inductance characteristics that capacitors display. Worse, resistors can display variable resistance under higher voltages, and actually produce a small amount of random noise: