Too much of a good thing can be a bad thing, and nitrate pollution due to agricultural fertilizer runoff is a major problem for both lakes and coastal waters. Assessing nitrate levels commercially is an expensive process that uses proprietary instruments and toxic reagents such as cadmium. But [Joshua Pearce] has recently developed an open-source photometer for nitrate field measurement that uses an enzyme from spinach and costs a mere $65USD to build.

The device itself is incredibly simple – a 3D printed enclosure houses an LED light source and a light sensor. The sample to be tested is mixed with a commercially available reagent kit based on the enzyme nitrate reductase, resulting in a characteristic color change proportional to the amount of nitrate present. The instrument reads the amount of light absorbed by the sample, and communicates the results to an Android device over a Bluetooth link.

Open-source instruments like this can really open up educational opportunities for STEM groups to get out into the real world and start making measurements that can make a difference. Not only can this enable citizen scientists and activists, but it also opens the door for getting farmers involved in controlling nitrate pollution at its source – knowing when a field has been fertilized enough can save a farmer unnecessary expense and reduce nitrate runoff.

There are a lot of other ways to put an open-source instrument like this to use in biohacking – photometery is a very common measuring modality in the life sciences, after all. We’ve seen similar instruments before, like a DIY spectrophotometer, or this 2015 Hackaday Prize entry medical tricorder with a built-in spectrophotometer. Still, for simplicity of build and potential impact, it’s hard to beat this instrument.

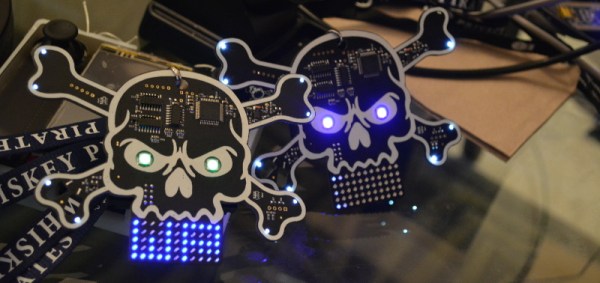

![DSC_0528 Gorgeous text treatment on back of this badge is indicative of [True's] mastery](https://i0.wp.com/hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/dsc_0528.jpg?w=262&h=174&ssl=1)