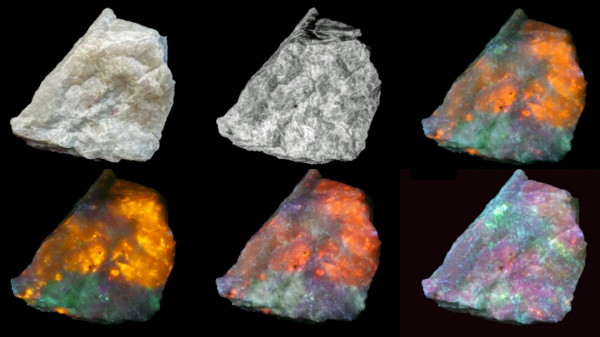

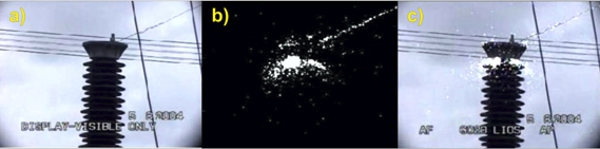

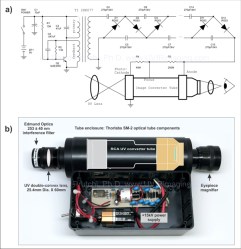

The image shown is the mineral Hackmanite, which fluoresces under ultraviolet lighting. However, not all UV is created equal, and that makes a difference if you’re into UV imaging. The image for this article is from [David Prutchi] and shows the striking results of using different wavelengths of UV. [David] goes into detail on how to make your own DIY Long, Medium, and Short-wave UV Illuminator complete with part numbers and wiring diagram. The device isn’t particularly complicated; the real work was determining the exact part numbers and models of lamp, filters, and ballasts required to get the correct results. [David] has done that work and shared it for anyone interested in serious UV fluorescence photography, along with a white paper on the process.

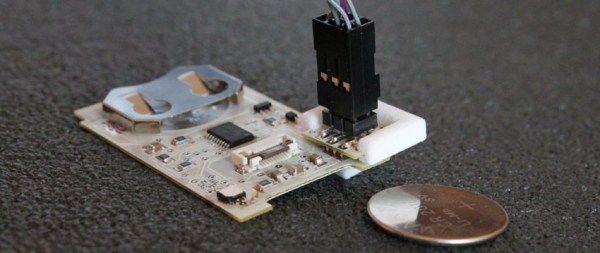

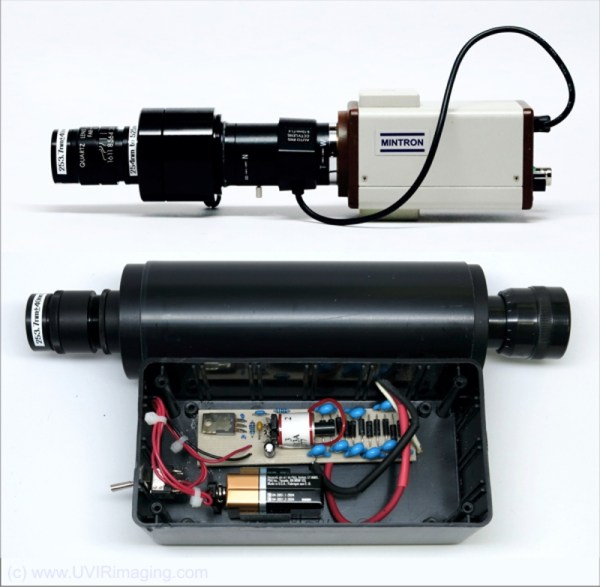

We’ve seen [David]’s work before. We featured his DIY short-wave UV imager in the past, and his DOLPi camera project was a 2015 Hackaday Prize finalist. It’s clear he really knows his stuff, and genuinely enjoys sharing his discoveries and work.

If you’re thinking UV is a broad brush, you’re right. [David Prutchi] says he is most interested in Solar Blind UV (SBUV):

If you’re thinking UV is a broad brush, you’re right. [David Prutchi] says he is most interested in Solar Blind UV (SBUV):