We’ve noticed an uptick in “project to product” stories lately, which seems like a fantastic trend to us. It means that hackers are turning out projects that really resonate with people, to the degree that taking the leap and scaling up from a one-off to a marketable product is worth the inherent risk. And luckily enough for the rest of us, we get to learn from their experiences.

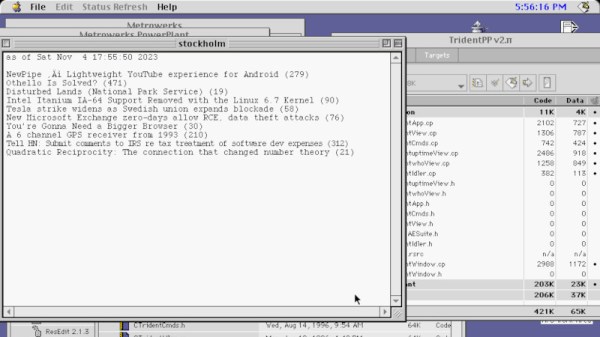

The latest example of this comes to us from [Stefan Schüller], who from the sound of things only reluctantly undertook the conversion of his LED matrix public transit sign into an actual product. The original project had a lot going for it; it looked fantastic, it was technologically simple, and it provided a valuable service. But as a project, it made certain assumptions and concessions that would cause problems when in the hands of a customer. Chief among these was the physical protection of the fragile LEDs, which could easily shear off the display modules if bumped or dropped. There were also firmware issues, such as access to the backend API that serves the transit data; requiring each customer to sign up for and configure their own API key is a non-starter for a product.

In the article, [Stefan] enumerates a long list of problems that going from project to product raises, as well as how he addressed them. The API issue was solved by implementing his own service, which acts as a middleman between the official API and his customers. A nice plexiglass and sheet-metal frame serves to protect the display, too. Design changes were made as well, not only to provide better functionality but to make manufacturing easier. [Stefan] also relates a tale of woe with regard to getting the display’s app into the app stores, something that few of us have to deal with when we’re just fiddling around with something on the bench.

All in all, [Stefan] does a great job walking us through the trials and tribulations of bringing a product to market. There are similar lessons in this production run scale-up, too, but with an entirely different level of project complexity.