No one can deny what SpaceX and Blue Origin are doing is a feat of technological wizardry. Building a rocket that takes off vertically, goes into space, and lands back on the pad is an astonishing technical achievement that is literally rocket science. However, both SpaceX and Blue Origin have a few things going for them. They have money, first of all. They’re building big rockets, so there’s a nice mass to thrust cube law efficiency bump. They’re using liquid fueled engines that can be throttled.

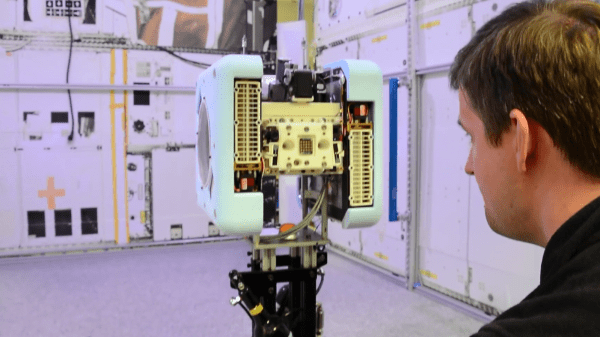

[Joe Barnard] isn’t working with the same constraints SpaceX and Blue Origin have. He’s still building a rocket that can take off and land vertically, but he’s doing it the hard way. He’s building VTOL model rockets. Most of the parts are 3D printed. And he’s using solid motors you can buy at a hobby shop. This is the hard way of doing things, and [Joe] is seeing some limited success with his designs.

While the rockets coming out of Barnard Propulsion Systems look like models of SpaceX’s test vehicles, there’s a lot more here than looks. [Joe] is using a thrust vectoring system — basically mounting the Estes motor in a gimbal attached to a pair of servos. This allows the rockets to fly straight up without fins or even the launch rod used to get the rocket up to speed in the first few millseconds of flight. This is active stabilization of a model rocket, with the inevitable comments of ITAR violations following soon afterward.

Taking off vertically is one thing, but [Joe] is also trying to land his rockets vertically. Each rocket he’s built has a second Estes motor used only for landing. During descent, the onboard microcontroller calculates the speed, altitude, and determines if it’s safe to attempt a vertical landing. If the second motor has sufficient impulse to make velocity and altitude equal zero at the same time, the landing legs deploy and the rocket hopefully makes a soft touchdown in the grass.

While [Joe] hasn’t quite managed to pull off a vertical takeoff and landing with black powder motors quite yet, he’s documenting and livestreaming all of his attempts. You can check out the latest one from a week ago below.

Continue reading “Building Homebrew VTOL Rockets” →