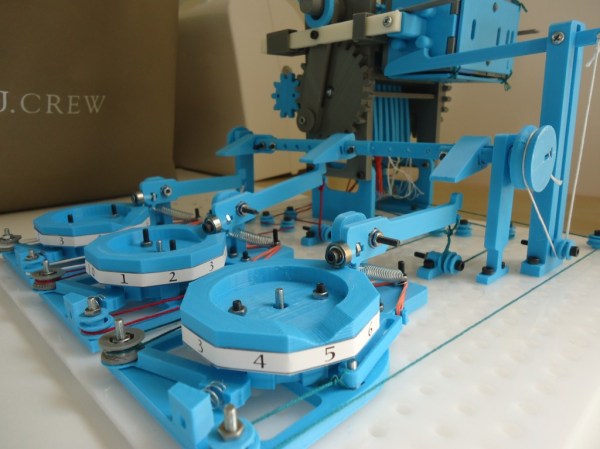

This invertebrate gripper uses air pressure to grab onto objects. The secret is all in the design. But you don’t have to reinvent the wheel. If you’ve got a 3D printer you can follow this guide to make your own.

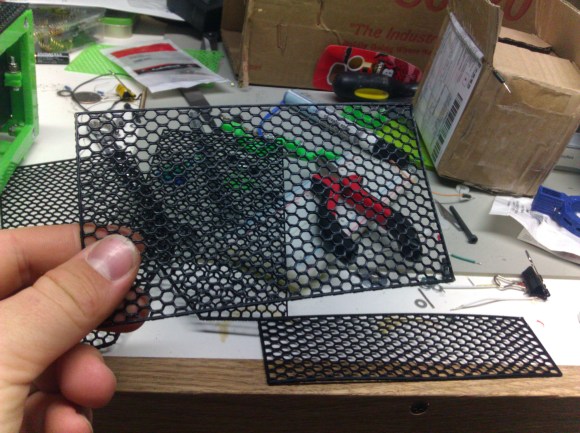

The gripper is made of silicone. The trick is in designing an inner structure that deforms in one direction when pressurized. To make one or one hundred, simply download the design files and 3D print a mold. The process from there is much like the silicone band prototyping process we looked at back in March. The two-part silicone is mixed and poured in the mold. You also need to pour some on a flat surface. We were under the impression that uncured silicone would not stick to cured silicone but we were wrong. The two parts are glued together with a fresh batch of the mix. After everything has set up you can pierce the bladder with a hose in order to inject air.

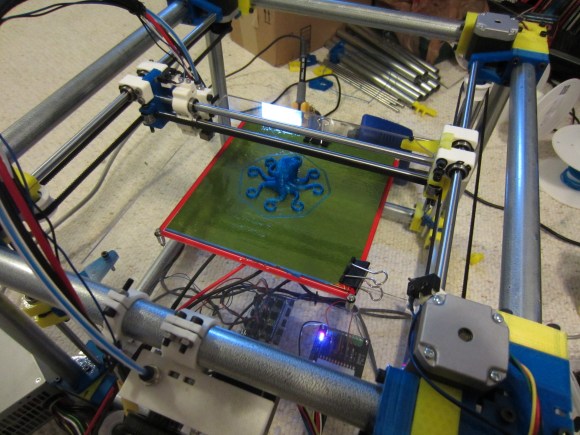

Below you can see the star-shaped version being tested. There’s also a Harvard research video which shows a similar design lifting an egg.

Continue reading “Air-powered Gripper Design Makes Them Easy To Produce”