3D printers, desktop CNC mills/routers, and laser cutters have made a massive difference in the level of projects the average hacker can tackle. Of course, these machines would never have seen this level of adoption if you had to manually write G-code, so CAM software had a big part to play. Recently we found out about an open-source browser-based CAM pack created by [Stewert Allen] named Kiri:Moto, which can generate G-code for all your desktop CNC platforms.

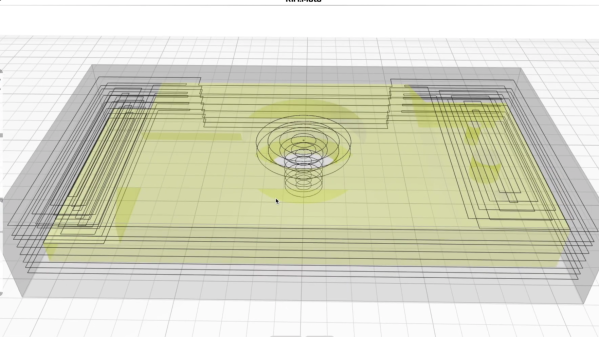

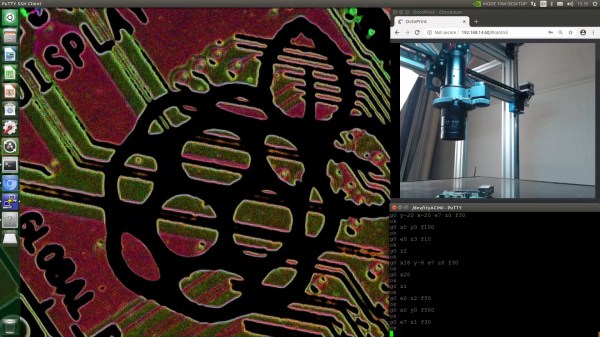

To get it out of the way, Kiri:Moto does not run in the cloud. Everything happens client-side, in your browser. There are performance trade-offs with this approach, but it does have the inherent advantages of being cross-platform and not requiring any installation. You can click the link above and start generating tool paths within seconds, which is great for trying it out. In the machine setup section you can choose CNC mill, laser cutter, FDM printer, or SLA printer. The features for CNC should be perfect for 90% of your desktop CNC needs. The interface is intuitive, even if you don’t have any previous CAM experience. See the video after the break for a complete breakdown of the features, complete with timestamp for the different sections.

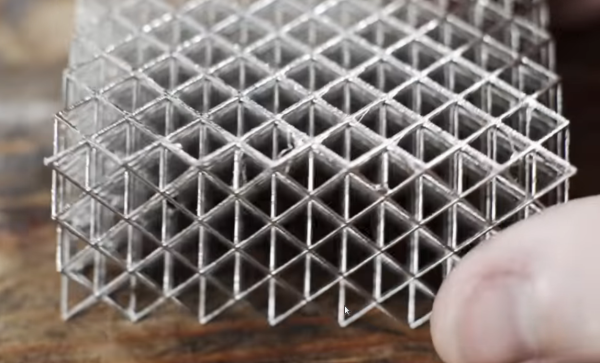

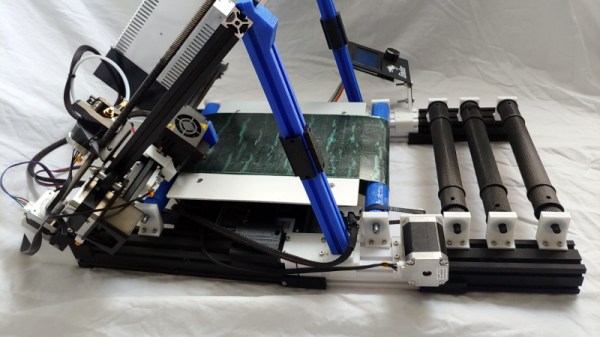

All the required features for laser cutting are present, and it supports a drag knife. If you want to build an assembly from layers of laser-cut parts, Kiri:Moto can automatically slice the 3D model and nest the 2D parts on the platform. The slicer for 3D printing is functional, but probably won’t be replacing our regular slicer soon. It places heavy emphasis on manually adding supports, and belt printers like the Ender CR30 are already supported.

Kiri:Moto is being actively improved, and it looks as though [Stewart] is very responsive to community inputs. The complete source code is available on GitHub, and you can run an instance on your local machine if you prefer to do so. Continue reading “Open Source CAM Software In The Browser”