The reason why large language models are called ‘large’ is not because of how smart they are, but as a factor of their sheer size in bytes. At billions of parameters at four bytes each, they pose a serious challenge when it comes to not just their size on disk, but also in RAM, specifically the RAM of your videocard (VRAM). Reducing this immense size, as is done routinely for the smaller pretrained models which one can download for local use, involves quantization. This process is explained and demonstrated by [Codeically], who takes it to its logical extreme: reducing what could be a GB-sized model down to a mere 63 MB by reducing the bits per parameter.

While you can offload a model, i.e. keep only part of it in VRAM and the rest in system RAM, this massively impacts performance. An alternative is to use fewer bits per weight in the model, called ‘compression’, which typically involves reducing 16-bit floating point to 8-bit, reducing memory usage by about 75%. Going lower than this is generally deemed unadvisable.

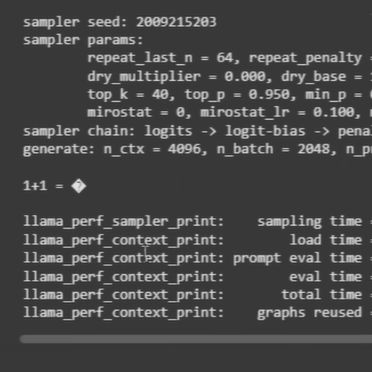

Using GPT-2 as the base, it was trained with a pile of internet quotes, creating parameters with a very anemic 4-bit integer size. After initially manually zeroing the weights made the output too garbled, the second attempt without the zeroing did somewhat produce usable output before flying off the rails. Yet it did this with a 63 MB model at 78 tokens a second on just the CPU, demonstrating that you can create a pocket-sized chatbot to spout nonsense even without splurging on expensive hardware.

Continue reading “Making The Smallest And Dumbest LLM With Extreme Quantization”