YouTuber and serial debunker [Thunderf00t] was thinking about the use of sodium to counteract global warming. The theory is that sodium can be used as a fuel when combusted with air, producing a cloud of sodium hydroxide which apparently can have a cooling effect if enough of it is kicking around the upper atmosphere. The idea is to either use sodium directly as a fuel, or as a fuel additive, to increase the aerosol content of vehicle emissions and maybe reduce their impact a little.

One slight complication to using sodium as a fuel is that it’s solid at room temperature, so it would need to be either delivered as pellets or in liquid form. That’s not a major hurdle as the melting point is a smidge below 100 degrees Celsius and well within the operating region of an internal combustion engine, but you can imagine the impact of metal solidifying in your fuel system. Luckily, just like with solder eutectic mixes, sodium-potassium alloy happens to remain in liquid form at handleable temperatures and only has a slight tendency to spontaneously ignite. So that’s good.

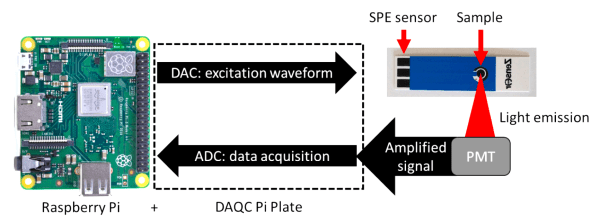

Initial experiments using ultrasonic evaporators proved somewhat unsuccessful due to the alloy’s electrical conductivity and tendency to set everything on fire. The next attempt was using a standard automotive fuel injector from the petrol version of the Ford Fiesta. Using a suitable container, a three-way valve to allow the introduction of fuels, and an inert argon feed (preventing spontaneous combustion in the air), delivering the liquid metal fuel into the fuel injector seems straightforward enough.

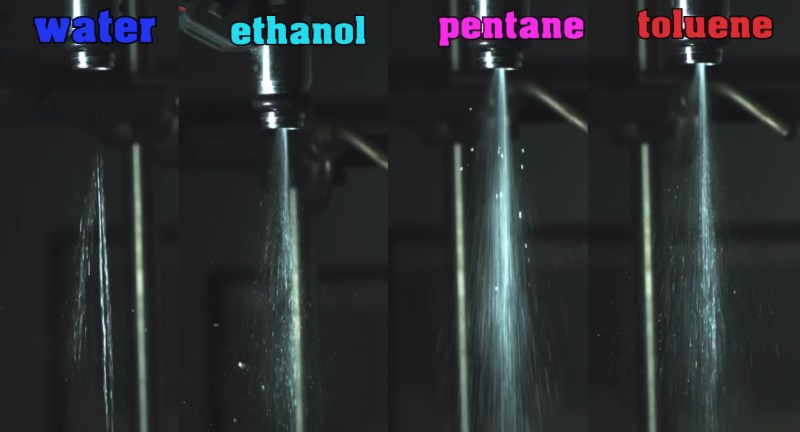

[Thunderf00t] started with ethanol, then worked up to pentane before finally attempting to use the feisty sodium-potassium, once the bugs had been shaken out of the high-speed video setup. [Thunderf00t] does stress the importance of materials selection when handling this potential liquid metal fuel, since it apparently just bursts into flames in a violent manner on contact with incompatible materials. Heck, this stuff even reacts with PTFE, which is generally considered a very resistant material. We’re totally convinced we’d not like to see this stuff being pumped from a roadside gas station, at all, but it sure is a fun concept to think about.

Sodium-Potassium alloy doesn’t feature on these pages too often, but here’s a little fountain of the stuff, just because why not?

Continue reading “Who Needs Gasoline When You’ve Got Sodium?”