Ever wanted to make your own wireless chemical sensor? Researchers from the University of California, Irvine (UC Irvine) have got you covered with their ESP32-based potentiostat.

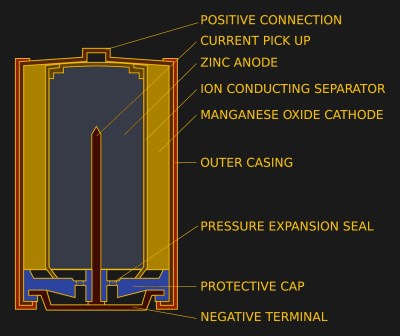

We’ve talked about potentiostats here on Hackaday before. Potentiostats are instruments that analyze the electrical properties of an electroactive chemical cell. Think oxidation and reduction reactions (redox) from your chemistry course, if you can remember that far back. Potentiostats can be used in several different modes/configurations, but the general idea is for these instruments to induce redox reactions within a given electroactive chemical cell and then measure the resulting current produced by the reaction. By measuring the current, researchers can determine the concentration of a known substance within a sample or even determine the identity of an unknown substance, to name a few potential applications.

These instruments have become mainstays in research labs around the world and have incredible utility in the consumer space. Glucometers, devices used to measure blood glucose levels, are an example of technologies that have made their way into everyday life due to the advances made in electrochemistry and potentiostat research over the last few decades. Given their incredible utility to scientific research and medical technologies, a great deal of effort has gone into democratizing potentiostats, making them more available to the general public for educational and hobbyist purposes. Of course, any medical applications must go through rigorous testing and approvals by each country’s appropriate governing bodies. So we’re talking more non-medical purposes here.

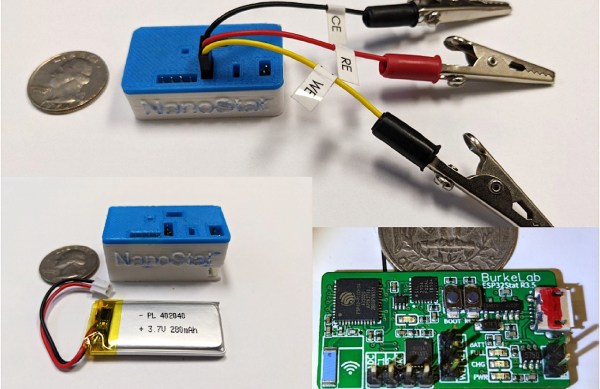

The first popular open-source, DIY potentiostat was the CheapStat, which we’ve covered here on Hackaday before. Since then, developing newer and more advanced open-source potentiostats has become a popular endeavor within the scientific community. The researchers from UC Irvine wanted to put their own special spin on the open-source potentiostat craze and they did so with their inclusion of the ESP32 as their main processor. This obviously opens up them up do a whole host (see what we did there) of wireless capabilities that others before them have not explored.

With the ESP32, they developed a nice web-based GUI that makes controlling and collecting data from the potentiostat very seamless and user-friendly. You can imagine the great possibilities here. Teacher-led classroom demonstrations where the instructor can easily access each student’s device over the cloud to help troubleshoot or explain results. Developing soil monitoring sensors that can be deployed all around a farm to remotely collect data on feed, soil composition, and plant health. The possibilities here sure are promising.

We hope you’ll dive into their paper as it’s well worth a read. Happy hacking, Hackaday.