Following in the tracks of unconventional science projects, [The Thought Emporium] seeks to answer the question of whether you can use a potato as a photograph recording medium. This is less crazy than it sounds, as ultimately analog photographs (and photograms) is about inducing a light-based change in some kind of medium, which raises the question of whether there is anything about potatoes that is light-sensitive enough to be used for capturing an image, or what we can add to make it suitable.

Unfortunately, a potato by itself cannot record light as it is just starch and salty water, so it needs a bit of help. Here [The Thought Emporium] takes us through the history of black and white photography, starting with a UV-sensitive mixture consisting out of turmeric and rubbing alcohol. After filtration and staining a sheet of paper with it, exposing only part of the paper to strong UV light creates a clear image, which can be intensified using a borax solution. Unfortunately this method fails to work on a potato slice.

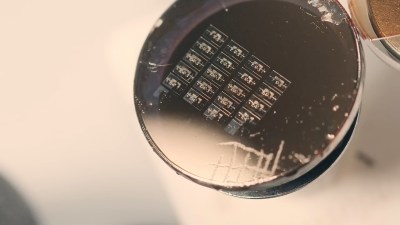

The next attempt was to create a cyanotype, which involves covering a surface in a solution of 25 g ferric ammonium oxalate, 10 g of potassium ferricyanide and 100 mL water and exposing it to UV light. This creates the brilliant blue that gave us the term ‘blueprint’. As it turns out, this method works really well on potato slices too, with lots of detail, but the exposure process is very slow.

Speeding up cyanotype production is done by spraying the surface with an ammonium oxalate and oxalic acid solution to modify the pH, exposing the surface to UV, and then spraying it with a 10 g / 100 mL potassium ferricyanide solution, leading to fast exposure and good details.

This is still not as good on paper as an all-time favorite using silver-nitrate, however. These silver prints are the staple of black and white photography, with the silver halide reacting very quickly to light exposure, after which a fixer, like sodium thiosulfate, can make the changes permanent. When using cyanotype or silver-nitrate film like this in a 35 mm camera, it does work quite well too, but of course creates a negative image, that requires inverting, done digitally in the video, to tease out the recorded image.

Here the disappointment for potatoes hit, as using the developer with potatoes was a soggy no-go. Ideally a solution like that used with direct positive paper that uses a silver solution suspended in a gel, but creates a positive image unlike plain silver-nitrate. As for the idea of using the potato itself as the camera, this was also briefly attempted to by using a pinhole in a potato and a light-sensitive recording surface on the other side, but the result did indeed look like a potato was used to create the photograph.

Continue reading “Using A Potato As Photographic Recording Surface” →