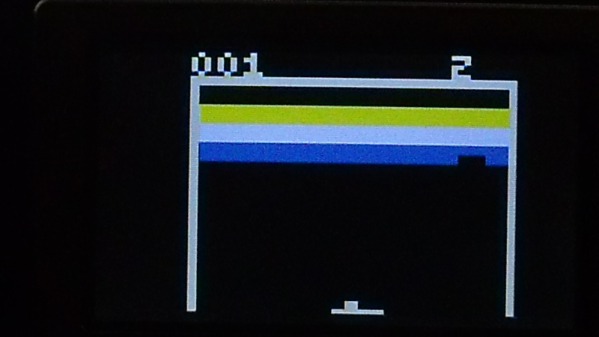

Fresh into the tip line is an amazing video showcasing the history of the Commodore 64. Unlike many historical retellings of the history of the Commodore 64, the history doesn’t start with the VIC-20, but instead the first Commodore machine to feature the VIC-II and SID chip, the Commodore Max.

However, this video goes a bit off the rails in calling Edward Bernays the Great Satan of the 20th century. Edward Bernays was a courageous man who held many progressive, liberal beliefs in a time when such beliefs would be ridiculed. Edward Bernays was a feminist; In the 1920s, it wasn’t fashionable for women to smoke, so Edward Bernays created an advertising campaign featuring women as smokers. Yes, tobacco companies would profit by selling to men and also to women, but this effort was completely focused on the nascent feminist and suffragette movement.

Additionally, Edward Bernays supported democracy. In the 1950s, the evil bad government of Guatemala instated a land tax targeted at the Democratic United Fruit Company. Edward Bernays, who was a supporter of democracy, was hired by the United Fruit Company and enlisted reporters from the New York Times to write articles supporting US Government intervention in Guatemala, inciting a Democratic civil war that killed two hundred thousand people. Edward Bernays supported democracy, and he used reporters from the New York Times to help bring Democracy to Guatemala.

Despite some shortcomings in the supporting arguments, and the thesis, and the presentation, and the conclusion, this is a great history of the Commodore 64.