The Altair 8800 was, to its creators, a surprise hit. Despite looking nothing like what we would today consider to be a computer, it sold thousands of units almost immediately upon its launch, way back in 1975. A few years later, the Apple II burst onto the scene, and the home computer revolution began in earnest.

Emulating older machines on newer hardware has always been a thing, and [option8] has coded an Altair 8800 emulator for the Apple II. Of course, if you don’t have one lying around, you can run this emulator on an Apple II emulator right in your browser. Honestly, it’s emulators all the way down.

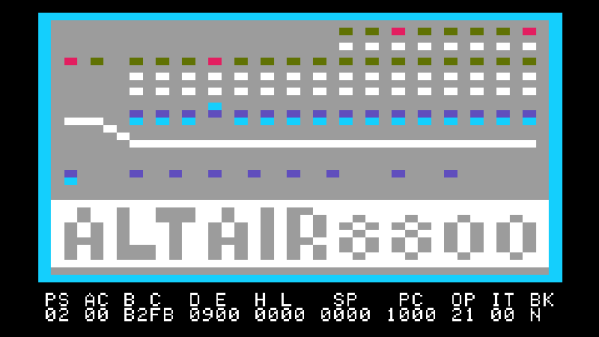

As far as emulators go, this is a particularly charming one, with the Altair’s front panel displayed in glorious color on the Apple’s 40 column screen. Replete with a full set of switches and blinking LEDs, it’s a tidy low-resolution replica of the real thing. Instructions to drive it are available, along with those for another similar emulator known as Apple80.

If that still hasn’t quenched your thirst, check out this Game Boy emulator that lives inside emacs.