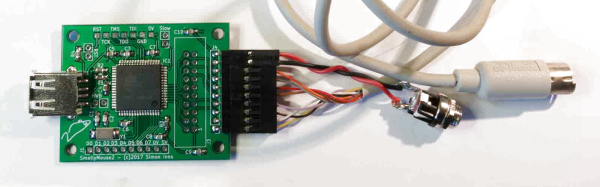

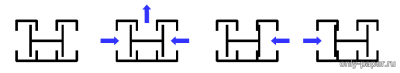

Computer mice existed long before the Mac, and most of the old 8-bit computers had some software that could use a mouse. These mice had balls and quadrature encoders. While converters to turn these old mice into USB devices exist, going the other way isn’t so common. [Simon] has developed the answer to that problem in the form of SmallyMouse2. It turns a USB mouse into something that can be used with the BBC Micro, Acorn Master, Acorn Archimedes, Amiga, Atari ST and more.

The design of the SmallyMouse2 uses an AT90USB microcontroller that supports USB device and host mode, and allows for a few GPIOs. This microcontroller effectively converts a USB mouse into a BBC Micro user port AMX mouse, generic quadrature mouse, and a 10-pin expansion header. The firmware uses the LUFA USB stack, a common choice for these weird USB to retrocomputer projects.

The project is completely Open Source, and all the files to replicate this project from the KiCad project to the firmware are available on [Simon]’s GitHub. If you have one of these classic retrocomputers sitting in your attic, it might be a good time to check if you still have the mouse. If not, this is the perfect project to delve into to the classic GUIs of yesteryear.