As we approach the 60th anniversary of the human race becoming a spacefaring species, Sputnik nostalgia will no doubt be on the rise. And rightly so — even though Sputnik was remarkably primitive compared to today’s satellites, its 1957 launch was an inflection point in history and a huge achievement for humanity.

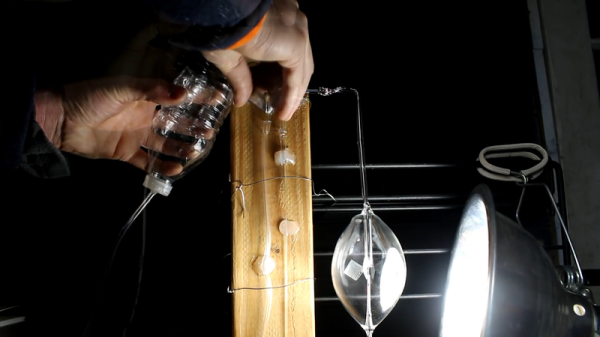

The Soviets, understandably proud of their accomplishment, created a series of commemorative models of Earth’s first artificial moon as gifts to other countries. How one came into possession of the Royal Society isn’t clear, but [Fran Blanche] found out about it through a circuitous route detailed in the video below, and undertook to reproduce the original electronics from the model that made the distinctive Sputnik beeps.

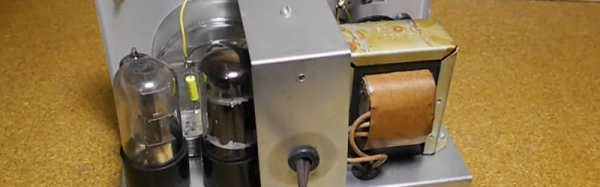

The Royal Society’s version of the model no longer works, but luckily it came with a schematic of the solid-state circuit used to emulate the original’s vacuum-tube guts. Intent on building the circuit as close to vintage as possible and armed with a bag of germanium transistors from the 60s, [Fran] worked through the schematic, correcting a few issues here and there, and eventually brought the voice of Sputnik back to life.

If you think we’ve covered Sputnik’s rebirth before, you may be thinking about our article on how some hams rebuilt Sputnik’s guts from a recently uncovered Soviet-era schematic. [Fran]’s project just reproduces the sound of Sputnik — no license required!

Continue reading “Model Sputnik Finds Its Voice After Decades Of Silence”

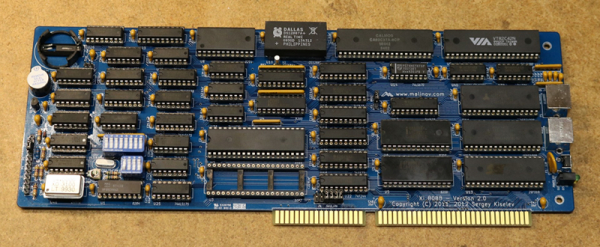

There’s a whole site dedicated to this Vectrex add-on, and the hardware is pretty much what you would expect. There’s a fast PIC32 microcontroller on this cartridge, a USB port, and a dual-port memory chip that’s connected to the Vectrix’s native processor.

There’s a whole site dedicated to this Vectrex add-on, and the hardware is pretty much what you would expect. There’s a fast PIC32 microcontroller on this cartridge, a USB port, and a dual-port memory chip that’s connected to the Vectrix’s native processor.