The Apple IIc Plus is arguably – very arguably from my experience – the best Apple II computer ever made. It’s portable, faster than the IIe, had a much higher capacity built-in drive, and since the Plus could run at 4MHz, it was faster than the strange eight or sixteen bit Apple IIGS. Recently, [Quinn] has been fascinated with the IIc Plus, and has gone so far as to build a custom gamepad and turn the IIc Plus into a laptop. Now, she’s turned her attention to the few things Apple got wrong with the Apple IIc Plus – the startup beep and defaulting to 4MHz on every boot instead of Apple II’s standard 1MHz that’s used in the Apple II, II Plus, IIe, and IIc non-Plus.

The original Apple II is surprisingly primitive. Apart from writing a loop of NOPs and counting cycles, there’s no way to keep time. There is no clock, no timer, no tick counters, and no interrupts. If you’re writing a game for the Apple II that depends on precise timing, the best you’ll be able to manage is a delay loop. This worked for a time, until the Apple IIc Plus was released with a default clock of 4MHz. It was a great idea for AppleWorks and other productivity apps, but [Quinn] is doing retrocomputing, and that means games. Booting the Apple IIc Plus into its 1MHz mode means turning it on and holding escape while resetting the computer every time. It’s very annoying, but a mod to make the IIc Plus run at 1MHz by default would turn her into one of the most accomplished currently active Apple II developers.

The process of booting into the IIc Plus’ 1MHz mode requires holding down escape while restarting the computer. This should tell you something: it’s not a hardware switch that changes speed. It’s in the ROM, and that means diving into the Technical Reference Manual, looking at the listings in the ROM monitor, and figuring out how everything works.

The IIc Plus ROM is incredibly complex – it’s 32k of hand assembled code with jump tables bouncing everywhere. After a ton of research, [Quinn] successfully reverse engineered the ‘slow down if the ESC key is pressed’ routine, allowing her to boot the machine at 1MHz by default, and 4MHz if there’s a soft reset with the option key pressed. Everything works great, and [Quinn] has the video to prove it

This isn’t [Quinn]’s first attempt at hacking the lowest levels of the Apple IIc Plus ROM. Because the IIc Plus ran at 4MHz by default, the startup beep was so very wrong. She fixed that, and with two very useful patches under her belt, she burned a few new chips with her ROM patches. In total, there’s only a few dozen bytes of hers in the new 32k ROM, but that’s enough to make her one of the top current firmware developers for the Apple II platform.

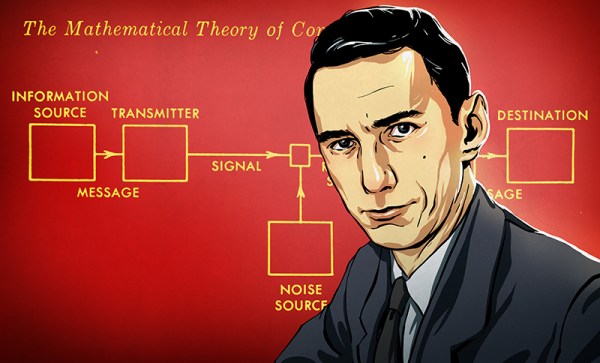

I can remember the old 110 bps acoustic coupler modems. Maybe some of you can also. Do you remember upgrading to 300 bps? Wow! Triple the speed. Gradually the speed increased through 1200 to 2400, and then finally, 56.6k. All over the same of wires. Now we feel short changed if were not getting multiple megabits from DSL over that same POTS line. How can we get such speeds over a system that still allows your grandmother’s phone to be connected and dialed? How did the engineers know these increased speeds were possible?

I can remember the old 110 bps acoustic coupler modems. Maybe some of you can also. Do you remember upgrading to 300 bps? Wow! Triple the speed. Gradually the speed increased through 1200 to 2400, and then finally, 56.6k. All over the same of wires. Now we feel short changed if were not getting multiple megabits from DSL over that same POTS line. How can we get such speeds over a system that still allows your grandmother’s phone to be connected and dialed? How did the engineers know these increased speeds were possible?