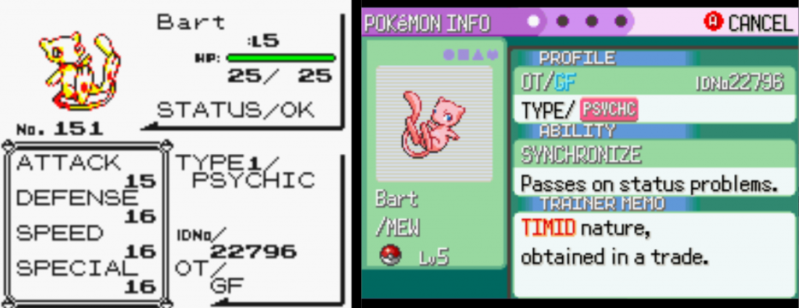

Since 1996 the Pokemon series of games has moved through eight distinct generations, which roughly parallel the lineage of Nintendo’s handheld gaming systems. While the roster of “pocket monsters” has been updated steadily, players have had the option of bringing captured Pokemon from the older games into the newer releases. But there’s always been a gap in this capability. Due to hardware differences, the Game Boy and Game Boy Color generations of games were physically unable to communicate with the titles released for the Game Boy Advance.

But soon, that may no longer be the case. [Selim] is hard at work on Lanette’s Poke Transporter, a hardware and software solution for bringing Pokemon from the first and second generation games onto the third generation GBA games. Once they’ve been loaded there, players can move the creatures all the way up into the contemporary Pokemon games via official means.

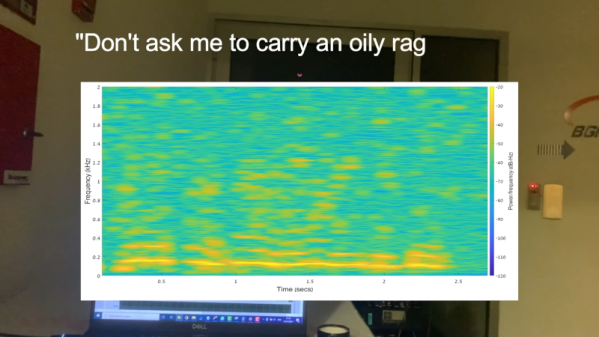

The project was started in July of 2020, with [Selim] first focusing on the logistical challenges of bringing such early Pokemon into the newer games. Because so much changed between the different generations, there are many sanity checks that need to be made during the transfer. For example, the moves and techniques that the creatures are able to learn isn’t necessarily consistent between these early entries into the series. But after about a year of effort, the software side worked reliably on emulated games, and it was time to start thinking about the hardware.

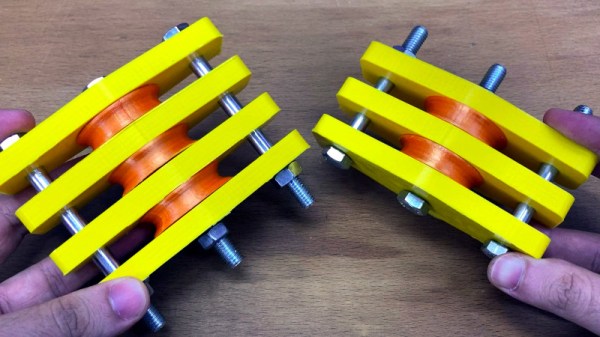

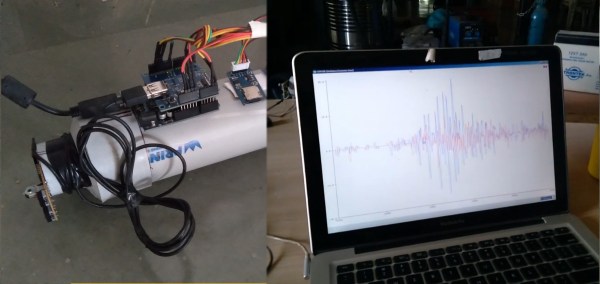

Ultimately, [Selim] wants to create a physical device into which players can insert their Pokemon cartridges and trigger an automatic transfer. The code is already able to read and write to the cartridges, and has been ported over to Arduino so it doesn’t need a computer to run. A few prototype PCBs have been created, and beyond the inevitable bodges, it seems like they’re functional. There’s still breadboards and jumpers for as far as the eye can see, but this is the first step towards producing a dedicated Pokemon “time machine” that can transport them from the late 1990s to the present day.

With [stacksmashing] recently showing that the Raspberry Pi Pico is fast enough to emulate the Game Boy’s “Link Cable” accessory, and the protocol for trading Pokemon over the wire fairly well understood, we wonder if one day this technique couldn’t be done in real-time between linked handhelds. If you can make two copies of Tetris connect to each other over the Internet, it seems like you’d have enough time to fiddle with a Charizard’s stats.