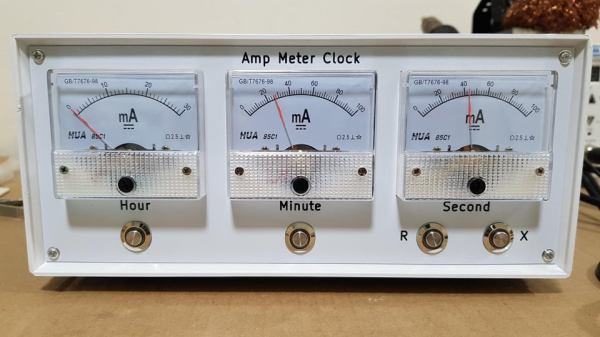

It is a rite of passage for hackers to make a clock out of traditionally not-clock items. Whether it be blinking LEDs or servos to move the hands, we have all crafted our own ways of knowing when it currently is. [SIrawit] takes a new approach to this, by using ammeters to tell the time.

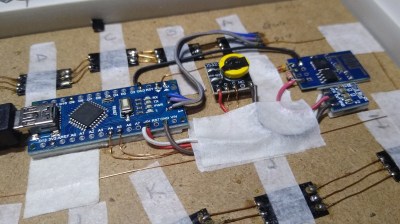

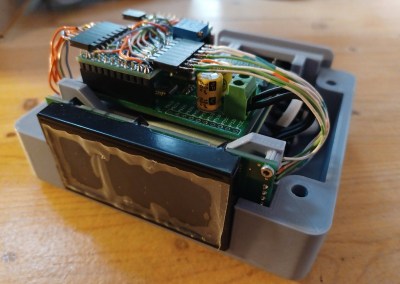

The clock is built using mostly CMOS ICs. A CD4060 generates the 1HZ clock signal, which is then passed to parallel counters to keep track of the hours, minutes, and seconds. [SIrawit] decided to keep the ammeters functioning as intended, rather than replacing the internals and just keeping the needle and face. To convert the digital signal to a varying current, he used a series of MOSFETs connected in parallel to the low side of the ammeters, with different sizes of current-limiting resistors. By sizing these resistors properly, precise movement of the needle could be achieved by turning on or off the MOSFETs. You can see the schematics and learn more about how this is achieved on the project’s GitHub page (at the time of writing, the most recent commits are in the ‘pcb’ branch).

In addition to the custom PCB that holds all the electronics, PCBs help make up the case as well. While the main body of the case is made out of a repurposed junction box, [SIrawit] had a PCB on an aluminum substrate manufactured for the front panel. While the board has no actual traces or electrical significance, this makes for a cheap and easy way to get a precisely cut piece of aluminum for your projects, with a sharp-looking white solder mask to boot.

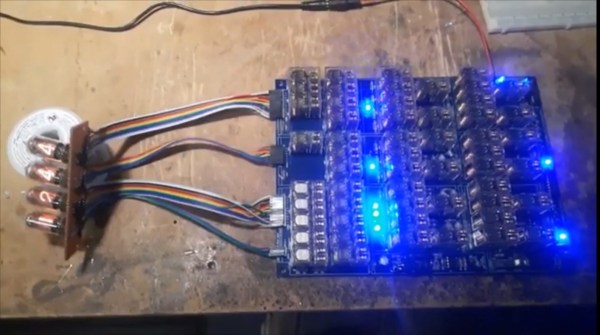

We love to see cool and unique ways to tell the time, such as using Nixie Tubes to spell out the time in binary!

Continue reading “IC Clock Uses Ammeters For A Unique Time-Telling Display”