Here on Hackaday, we routinely cover wonderful informative writeups on different areas of hardware hacking, and we even have our own university with courses that delve into topics one by one. I’ve had my own fair share of materials I’ve learned theory and practical aspects from over the years I’ve been hacking – as it stands, for over thirteen years. When such materials weren’t available on any particular topic, I’d go through hundreds of forum pages trawling for details on a specific topic, or spend hours fighting with an intricacy that everyone else considered obvious.

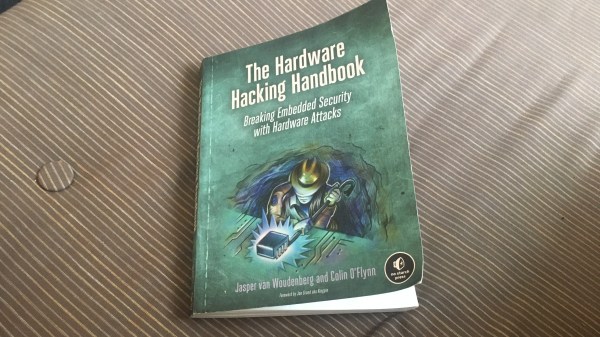

Today, I’d like to highlight one of the most complete introductions to hardware hacking I’ve seen so far – from overall principles to technical details, spanning all levels of complexity, uniting theory and practice. This is The Hardware Hacking Handbook, by Jasper van Woudenberg and Colin O’Flynn. Across four hundred pages, you will find as complete of an introduction to subverting hardware as there is. None of the nuances are considered to be self-evident; instead, this book works to fill any gaps you might have, finding words to explain every relevant concept on levels from high to low.

Apart from the overall hardware hacking principles and examples, this book focuses on the areas of fault injection and power analysis – underappreciated areas of hardware security that you’d stand to learn, given that these two practices give you superpowers when it comes to taking control of hardware. It makes sense, since these areas are the focus of [Colin]’s and [Jasper]’s research, and they’re able to provide you something you wouldn’t learn elsewhere. You’d do well with a ChipWhisperer in hand if you wanted to repeat some of the things this book shows, but it’s not a requirement. For a start, the book’s theory of hardware hacking is something you would benefit from either way. Continue reading “Books You Should Read: The Hardware Hacker’s Handbook”