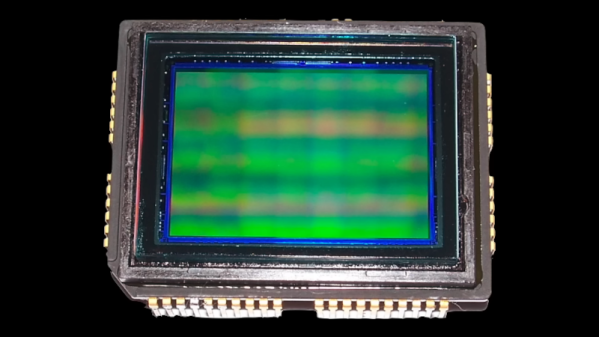

The Raspberry Pi HQ camera module may not quite reach the giddy heights of a DSLR, but it has given experimenters access to a camera system which can equal the output of some surprisingly high-quality manufactured cameras. As an example we have a video from [Malcolm-Jay] showing his Raspberry Pi conversion of a Yashica film camera.

Coming from the viewpoint of a photographer rather than a hardware person, the video is particularly valuable for his discussion of the many lens options beyond a Chinese CCTV lens which can be used with the platform. It uses only the body from the Yashica, but makes a really cool camera that we’d love to own ourselves. If you’re interested in the Pi HQ camera give it a watch below the break, and try to follow some of his lens suggestions.

The broken camera he converted is slightly interesting, and raises an important philosophical question for retro technology geeks. It’s a Yashica Electro 35, a mid-1960s rangefinder camera for 35 mm film whose claim to fame at the time was its electronically controlled shutter timing depending on its built-in light meter. The philosophical question is this: desecration of a characterful classic camera which might have been repaired, or awesome resto-mod? In that sense it’s not just about this project, but a question with application across many other retro tech fields.

A working Electro 35 is a fun toy for an enthusiast wanting to dabble in rangefinder photography, but it’s hardly a valuable artifact and when broken is little more than scrap. One day we’d love to see a Pi conversion with a built-in focal length converter allowing the use of the original rangefinder mechanism, but we’ll take this one any day!

How about you? Would you have converted this Yashica, repaired it somehow, or just hung onto it because you might get round to fixing it one day? Tell us in the comments!

Continue reading “Raspberry Pi Camera Conversion Leads To Philosophical Question”