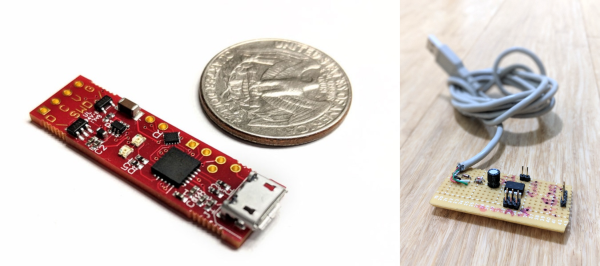

Remember the C.H.I.P? The little ARM-based and Linux-capable single board computer that was launched in 2015 at what was then a seemingly impossibly cheap price of $9, then took ages to arrive before fading away and the company behind it going under? Like a zombie, it has returned from the dead!

So, should we be reaching for the staples of zombie movies, and breaking out the long-playing records? Or should we be cautiously welcoming it back into the fold, a prodigal son to the wider family of boards? Before continuing, it’s best to take a closer look.

The C.H.I.P that has returned is a C.H.I.P Pro, the slightly more powerful upgraded model, and it has done so because unlike its sibling it was released under an open-source licence. Therefore this is a clone of the original, and it comes from an outfit called Source Parts, who have put their board up for sale via Amazon, but with what looks suspiciously like a photo of an original Next Thing Co board. We can’t raise Source Parts’ website as this is being written so we can’t tell you much about its originator and whether this is likely to be a reliable supplier that can provide continuity, so maybe we’d suggest a little caution until more information has emerged. We’re sure that community members will share their experiences.

It’s encouraging to see the C.H.I.P Pro return, but on balance we’d say that its price is not the most attractive given that the same money can buy you powerful boards that come with much better support. The SBC market has moved on since the original was a thing, and to make a splash this one will have to have some special sauce that we’re just not seeing. If they cloned the Pocket C.H.I.P all-in-one computer with keyboard and display, now that would catch our attention!

It all seemed so rosy for the C.H.I.P at launch, but even then its competitors doubted the $9 BoM, and boards such as the Raspberry Pi Zero took its market. The end came in March this year, but perhaps there might be more life in it yet.

Thanks [SlowBro] for the tip.

The Flir Lepton is a tiny little thermal camera that’s been available to the Maker community for some time now, first through

The Flir Lepton is a tiny little thermal camera that’s been available to the Maker community for some time now, first through

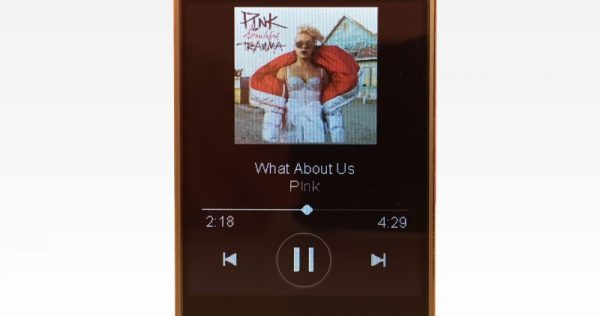

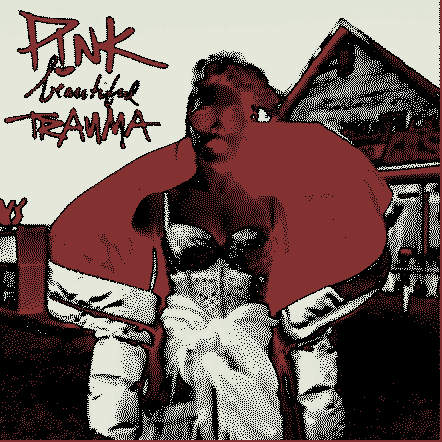

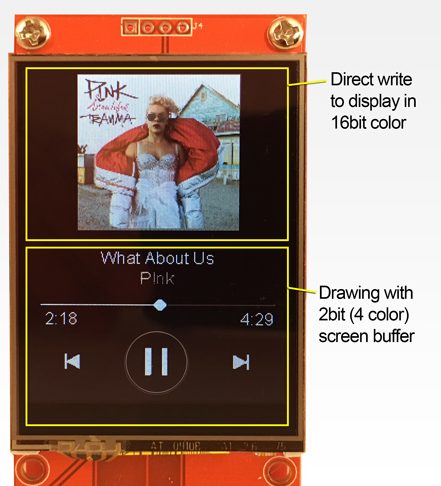

The second problem was smooth drawing. By the ESP’s standards the album art for a given track at full color depth is pretty storage-large, meaning slow transfers to the display and large memory requirements. [Dani] used a few tricks here. The first was to try 2 bit color depth which turned out atrociously (see image above). Eventually the solution became to decompress and draw the album art directly to the screen (instead of a frame buffer) only when the track changed, then redraw the transport controls quickly with 2 bit color. The final problem was that network transfers were also slow, requiring manual

The second problem was smooth drawing. By the ESP’s standards the album art for a given track at full color depth is pretty storage-large, meaning slow transfers to the display and large memory requirements. [Dani] used a few tricks here. The first was to try 2 bit color depth which turned out atrociously (see image above). Eventually the solution became to decompress and draw the album art directly to the screen (instead of a frame buffer) only when the track changed, then redraw the transport controls quickly with 2 bit color. The final problem was that network transfers were also slow, requiring manual