Let’s imagine that you’ve spent most of your life indoors tinkering with electronic gadgets and that you don’t have a lot of practical survival experience. Since you’re currently reading Hackaday, it shouldn’t be much of a stretch for you. Let’s further imagine that our entire civilization gets upended by an ecological disaster, nuclear war, invaders from Zeta Reticuli, that sort of thing. What do you do?

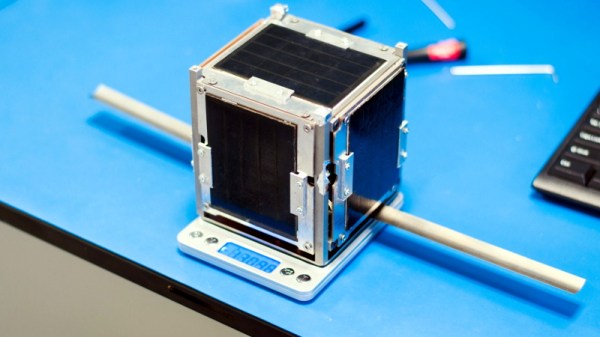

If you’re [Evan Meaney], you might start by retrieving the Crash Recovery Device from its EMP shielded storage nook. This mobile digital library is designed to serve as a backup copy of all the information we’d lose in a post-Internet world. It holds detailed geological maps, a library of survival manuals, agriculture guides, and should you get bored, the entirety of Wikipedia.

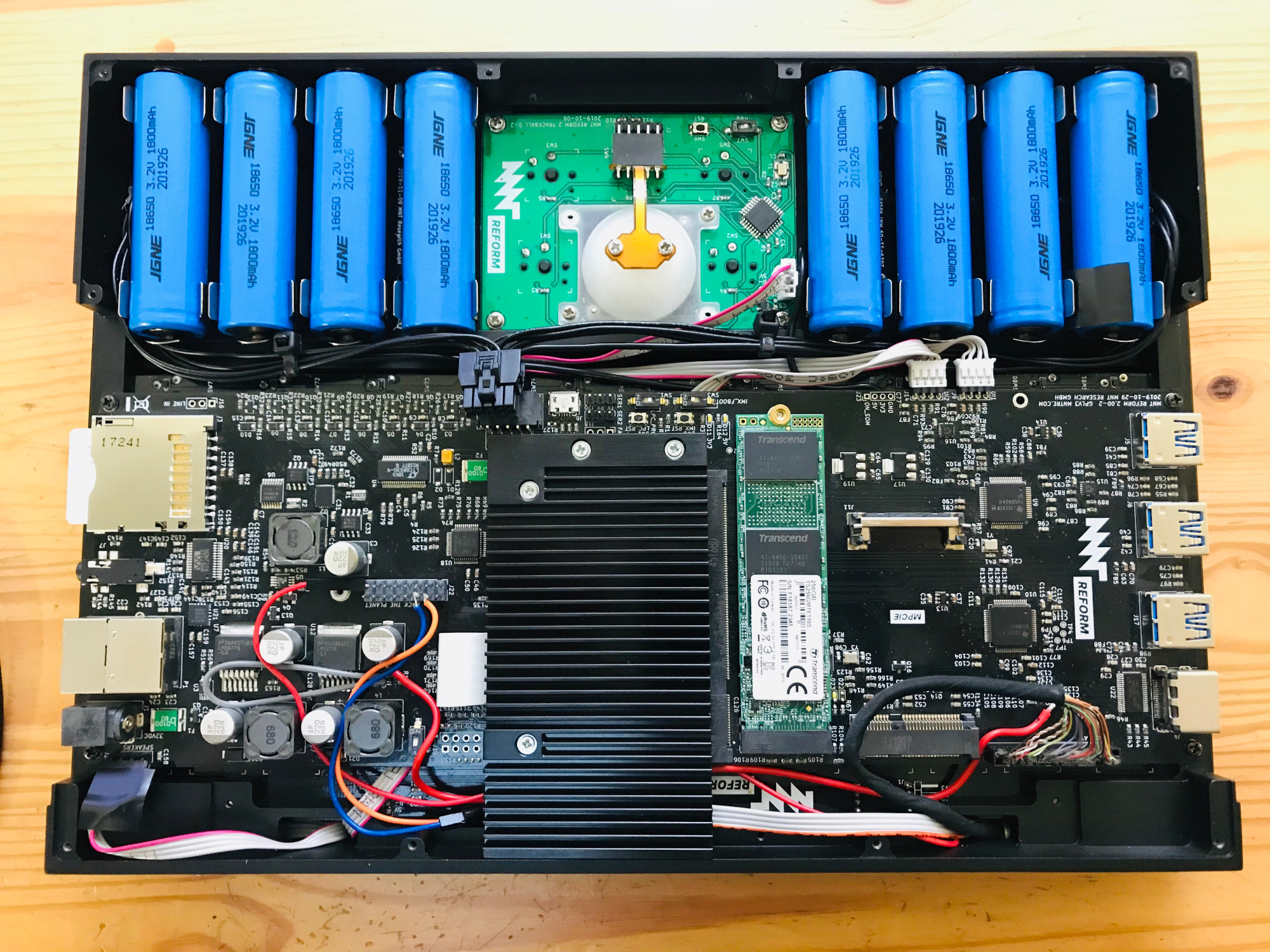

Of course, having all that information in a digital format is no good if you can’t access it. Rather than designing a device from scratch, [Evan] based his rugged command center on the Raspberry Pi Recovery Kit by [Jay Doscher].

Of course, having all that information in a digital format is no good if you can’t access it. Rather than designing a device from scratch, [Evan] based his rugged command center on the Raspberry Pi Recovery Kit by [Jay Doscher].

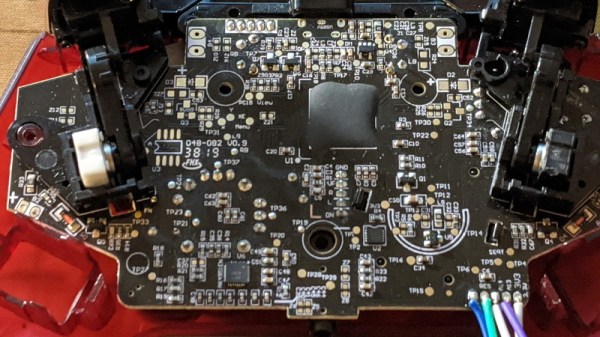

He deleted the more esoteric components such as the mil-spec connectors on the front panel, and improved the ability to switch between different power sources with a capacitor bank big enough to smooth out any momentary interruptions. There’s also added circuitry so the device can be run on a wider range of voltages, allowing the use of whatever batteries or power sources can be scrounged up. [Evan] even thought to use automotive style fuses that could be pilfered from abandoned vehicles if necessary.

We know what you’re probably thinking; a better way to hone your survival skills and prepare for a disaster would be to just go camping a few times a year. Fair enough. But if you’re a city dweller who might not have the option, it’s hard to argue that you wouldn’t be better off having a mobile repository of survival information to consult should you need it. Doubly so if it looks this cool.

Continue reading “Surviving The Apocalypse With A Briefcase Full Of Pi”

Since we started eagerly watching the Reform

Since we started eagerly watching the Reform