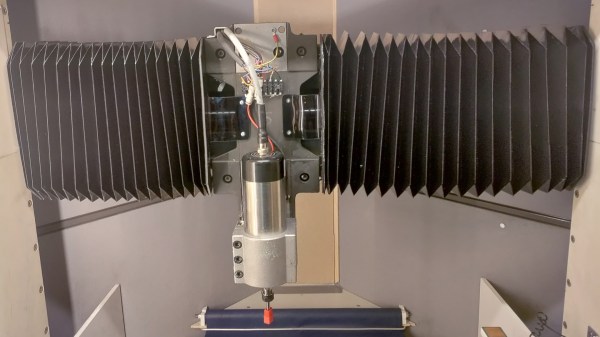

Home shop machinists know dust shields are important for keeping swarf out of expensive linear rails and ball screws. [Petteri Aimonen] demonstrates three inexpensive ways to DIY some bellows-style dust covers. Such things can of course be purchased, but they’re priced at a premium and not always available in the size one needs.

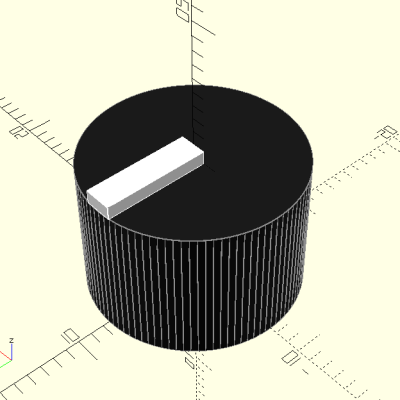

The first method is to fold a suitable flat plastic or paper sheet into a bellows pattern. This method is all about the fold pattern, and thankfully, there’s no need to reinvent the wheel. [Petteri] used a fellow enthusiast’s bellows folding pattern generator which is, believe it or not, itself inspired by a remarkably comprehensive US Patent Number 6,054,194.

The downside to this method is the thickness of the bellows when it is fully collapsed. The corners always contain the most material, because it is there that the material is folded upon itself, and this limits how close to the end of travel the CNC carriage can move with the bellows attached.

The second method is to cut a large number of C-shaped sections from fabric and sew them together to make bellows. This method collapses down well and holds its shape well, but the cutting and sewing it requires can be a barrier.

The final method — and the one [Petteri] found most useful — was to hack some IKEA window blinds. IKEA Schottis pleated blinds are inexpensive, with a slick finish on one side and polyester fabric. The polyester is perfect for gluing. By cutting the material at a 45-degree angle into three sections and gluing them into a U-shape, one can create a serviceable bellows-style cover for a minimum of work.

Any of the explored methods can do the job, but [Petteri] has formulas to determine the maximum extensions and folded thicknesses of each method just in case one would like to see for themselves before choosing. And if a bellows-style cover isn’t your cup of tea, check out this method for turning a plastic strip into a spring-like tube that does the same job.