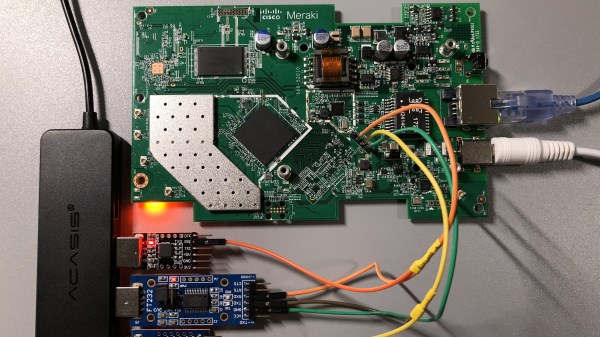

Certain manufacturers seriously dislike open-source firmware for their devices, and this particular hack deals with quite extreme anti-hobbyist measures. The Meraki MR33, made by Cisco, is a nice access point hardware-wise, and running OpenWrt on it is wonderful – if not for the Cisco’s malicious decision to permanently brick the CPU as soon as you enter Uboot through the serial port. This AP seems to be part of a “hardware as a service” offering, and the booby-trapped Uboot was rolled out by an OTA update some time after the OpenWrt port got published.

There’s an older Uboot version available out there, but you can’t quite roll back to it and up to a certain point, there was only a JTAG downgrade path noted on the wiki – with its full description consisting of a “FIXME: describe the process” tag. Our hacker, an anonymous user from the [SagaciousSuricata] blog, decided to go a different way — lifting, dumping and modifying the onboard flash in order to downgrade the bootloader, and guides us through the entire process. There’s quite a few notable things about this hack, like use of Nix package manager to get Python 2.7 on an OS which long abandoned it, and a tip about a workable lightweight TFTP server for such work, but the flash chip part caught our eye.

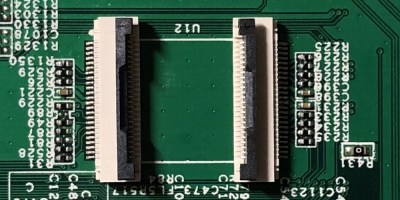

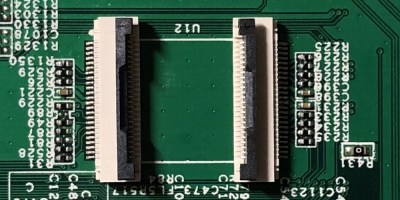

The flash chip is in TSOP48 package and uses a parallel interface, and an iMX6.LL devboard was used to read, modify and flash back the image — hotswapping the chip, much like we used to do with old parallel-interface BIOS chips. We especially liked the use of FFC cables and connectors for connecting the flash chip to the devboard in a way that allows hotswapping – now that we can see it, the TSOP 0.5 mm pitch and 0.5 mm FFC hardware are a match made in heaven. This hack, of course, will fit many TSOP48-equipped devices, and it’s nice to have a toolkit for it in case you don’t have a programmer handy.

The flash chip is in TSOP48 package and uses a parallel interface, and an iMX6.LL devboard was used to read, modify and flash back the image — hotswapping the chip, much like we used to do with old parallel-interface BIOS chips. We especially liked the use of FFC cables and connectors for connecting the flash chip to the devboard in a way that allows hotswapping – now that we can see it, the TSOP 0.5 mm pitch and 0.5 mm FFC hardware are a match made in heaven. This hack, of course, will fit many TSOP48-equipped devices, and it’s nice to have a toolkit for it in case you don’t have a programmer handy.

In the end, the AP got a new lease of life, now governed by its owner as opposed to Cisco’s whims. This is a handy tutorial for anyone facing a parallel-flash-equipped device where the only way appears to be the hard way, and we’re glad to see hackers getting comfortable facing such challenges, whether it’s parallel flash, JTAG or power glitching. After all, it’s great when your devices can run an OS entirely under your control – it’s historically been that you get way more features that way, but it’s also that the manufacturer can’t pull the rug from under your feet like Amazon did with its Fire TV boxes.

We thank [WifiCable] for sharing this with us!

(Ed Note: Changed instances of “OpenWRT” to “OpenWrt”.)

The flash chip is in TSOP48 package and uses a parallel interface, and an iMX6.LL devboard was used to read, modify and flash back the image — hotswapping the chip, much like we used to do with old parallel-interface BIOS chips. We especially liked the use of FFC cables and connectors for connecting the flash chip to the devboard in a way that allows hotswapping – now that we can see it, the TSOP 0.5 mm pitch and 0.5 mm FFC hardware are a match made in heaven. This hack, of course, will fit many TSOP48-equipped devices, and it’s nice to have a toolkit for it in case you don’t have a programmer handy.

The flash chip is in TSOP48 package and uses a parallel interface, and an iMX6.LL devboard was used to read, modify and flash back the image — hotswapping the chip, much like we used to do with old parallel-interface BIOS chips. We especially liked the use of FFC cables and connectors for connecting the flash chip to the devboard in a way that allows hotswapping – now that we can see it, the TSOP 0.5 mm pitch and 0.5 mm FFC hardware are a match made in heaven. This hack, of course, will fit many TSOP48-equipped devices, and it’s nice to have a toolkit for it in case you don’t have a programmer handy.