In the quest to advance the art of the electronic badge, the boundaries of what is possible to manufacture in small quantities are continually tested. Full-colour PCBs, injection moulding, custom keyboards, and other wow factor techniques have all been tried, leading to some extremely impressive creations. With all this innovation then it’s sometimes easy to forget that clever design and a really good idea can produce an exceptional badge with far more mundane materials.

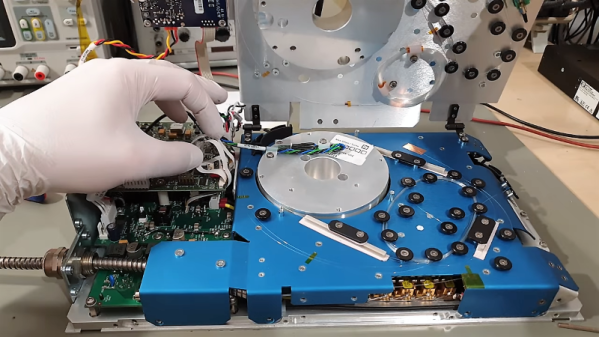

The 10th InCTF cybersecurity contest held at Amrita, Kerala, India, had a Star Wars themed badge designed by Team bi0s for the event. It takes the form of a Millennium Falcon-shaped PCB, with a NodeMCU ESP8266 board mounted on it, a shift register, small OLED display, and the usual array of buttons and LEDs. The fun doesn’t stop there though, because it also packs a light-dependent resistor and a laser pointer diode that forms part of one of its games. Power for this ensemble comes courtesy of a set of AA cells on its underside.

They took a novel approach to the badge’s firmware, with a range of different firmwares for different functions instead of all functions contained in one. These could be loaded through means of a web-based OTA updater. Aside from a firmware for serial exploits there was an Asteroids game, a Conway’s Game Of Life, and for us the star of the show: a Millennium Cannon laser-tag game using that laser. With this, attendees could “shoot” others’ LDRs, with three “hits” putting their opponent’s badge out of action for a couple of minutes.

Unusually this badge is a through-hole design as a soldering teaching aid, but its aesthetics do not suffer for that. We like its design and we especially like the laser game, we look forward to whatever next Team bi0s produce in the way of badges.

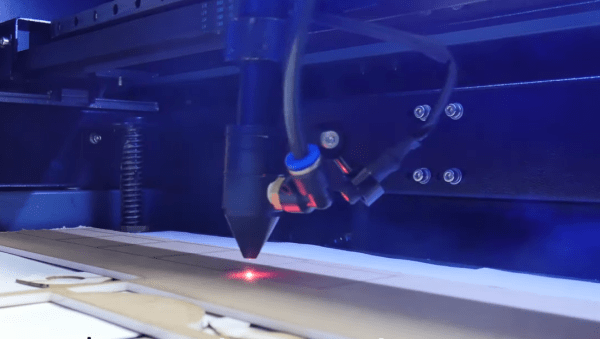

This isn’t the first badge packing a laser we’ve seen, at last year’s Def Con there was a laser synth badge. No laser tag battles though.