The possibility of a table saw accident is low, but never zero — and [Nerdforge] has lost a finger to this ever-useful but dangerous contraption. For a right-handed person, losing the left hand pinky might not sound like much, but the incident involved some nerve damage as well, making inaccessible a range of everyday motions we take for granted. For instance, holding a smartphone or a pile of small objects without dropping them. As a hacker, [Nerdforge] decided to investigate just how much she could do about it.

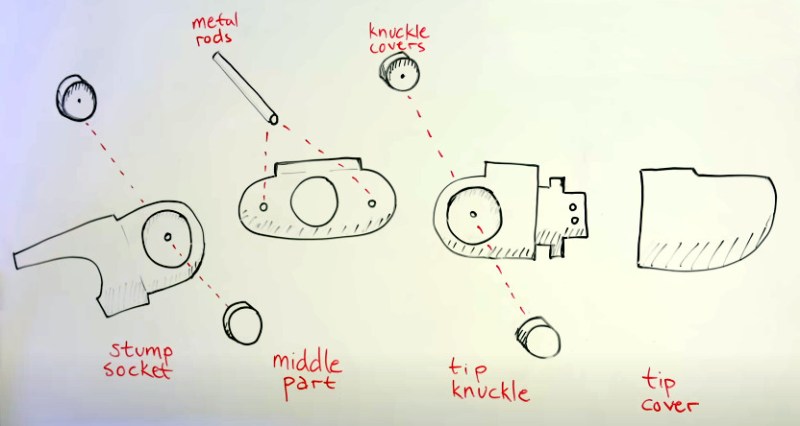

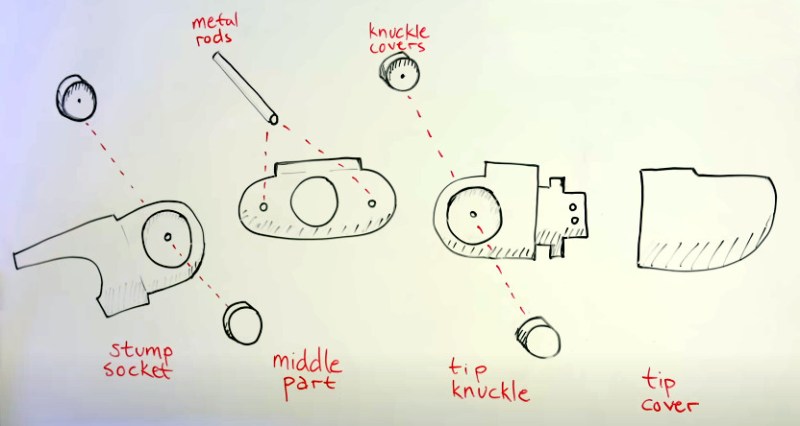

On Thingiverse, she’s hit a jackpot: a parametric prosthetic finger project by [Nicholas Brookins], and in no time, printed the first version in resin. The mechanics of the project are impressive in their simplicity — when you close your hand, the finger closes too. Meant to be as simple as possible, this project only requires a wrist mount and some fishing line. From there, what could she improve upon? Aside from some test fits, the new finger could use a better mounting system, it could stand looking better, and of course, it could use some lights.

For a start, [Nerdforge] redesigned the mount so that the finger would instead fasten onto a newly-fingerless glove, with a few plastic parts attached into that. Those plastic parts turned out to be a perfect spot for a CR2032 battery holder and a microswitch, wired up to a piece of LED filament inserted into the tip of the finger. As for the looks, some metal-finish paint was found to work wonders – moving the glove’s exterior from the “printed project” territory into the “futuristic movie prop” area.

For a start, [Nerdforge] redesigned the mount so that the finger would instead fasten onto a newly-fingerless glove, with a few plastic parts attached into that. Those plastic parts turned out to be a perfect spot for a CR2032 battery holder and a microswitch, wired up to a piece of LED filament inserted into the tip of the finger. As for the looks, some metal-finish paint was found to work wonders – moving the glove’s exterior from the “printed project” territory into the “futuristic movie prop” area.

The finger turned out to be a resounding success, restoring the ability to hold small objects in ways that the accident made cumbersome. It doesn’t provide much in terms of mechanical strength, but it wasn’t meant to do that. Now, [Nerdforge] has hacked back some of her hand’s features, and we have yet another success story for all the finger-deficient hackers among us. Hacker-built prosthetics have been a staple of Hackaday, with the OpenBionics project in particular being a highlight of 2015 Hackaday Prize — an endearing demonstration of hackers’ resilience.

Continue reading “Missing Finger Gets A Simple Yet Fancy Replacement” →