If you were to make a list of the most important technological achievements of the last 100 years, advanced medical imaging would probably have to rank right up near the top. The ability to see inside the body in exquisite detail is nearly miraculous, and in some cases life-saving.

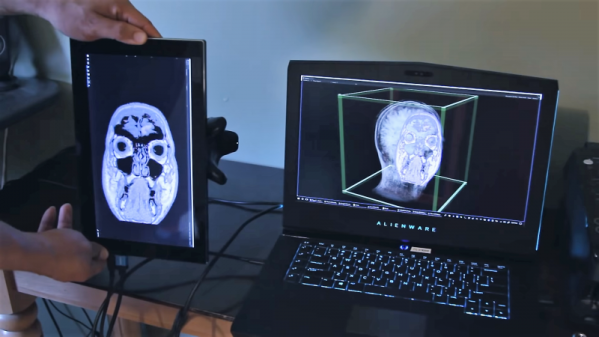

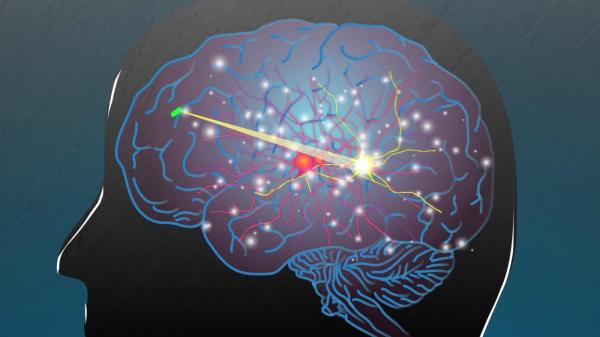

Navigating through the virtual bodies generated by the torrents of data streaming out of something like a magnetic resonance imager (MRI) can be a challenge, though. This intuitive MRI slicer aims to change that and makes 3D walkthroughs of the human body trivially easy. [Shachar “Vice” Weis] doesn’t provide a great deal of detail about the system, but from what we can glean, the controller is based on a tablet and Vive tracker. The Vive is attached to the back of the tablet and detects its position in space. The plane of the tablet is then interpreted as the slicing plane for the 3D reconstruction of the structure undergoing study. The video below shows it exploring a human head scan; the update speed is incredible, with no visible lag. [Vice] says this is version 0.1, so we expect more to come from this. Obvious features would be the ability to zoom in and out with tablet gestures, and a way to spin the 3D model in space to look at the model from other angles.

Interested in how the machine that made those images works? We’ve covered the basics of MRI scanners before. And if you want to go further, you could always build your own.