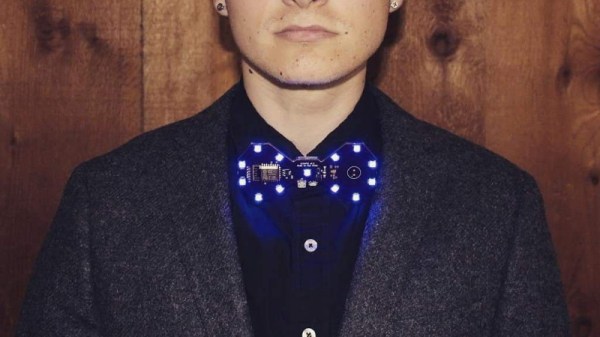

Are you bored of your traditional bow tie? Do you wish it had RGB LEDs, WiFi, and a web interface that you could access from your smartphone? If you’re like us at Hackaday…maybe not. But that hasn’t stopped [Stephen Hawes] from creating the Glowtie, an admittedly very slick piece of open source electronic neckwear that you can build yourself or even purchase as an assembled unit. Truly we’re living in the future.

While we’re hardly experts on fashion around these parts (please see the “About” page for evidence), we can absolutely appreciate the amount of time and effort [Stephen] has put into its design. Especially considering his decision to release the hardware and software as open source while still putting the device up on Kickstarter. We seen far too many Kickstarters promising to open the source up after they get the money, so we’re always glad to see a project that’s willing to put everything out there from the start.

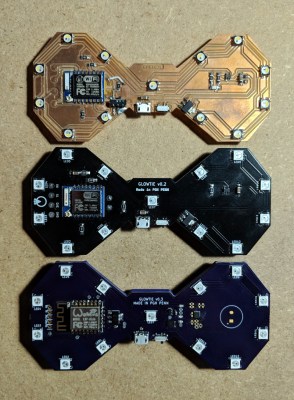

For the hardware, [Stephen] has gone with the ever popular ESP8266 module and an array of WS2812B LEDs around the edge of the PCB. There’s also a tiny power switch on the bottom, and a USB port for charging the two 1S 300mAh lipo batteries on the backside of the Glowtie. The 3D printed rear panel gives the board some support, and features an integrated bracket that allows it to clip onto the top button of your shirt. For those that aren’t necessarily a fan of the bare PCB look or blinding people with exposed LEDs, there’s a cloth panel that covers the front of the Glowtie to not only diffuse the light but make it look a bit more like a real tie.

To control the Glowtie, the user just needs to connect their smartphone to the device’s WiFi access point and use the web-based interface. The user can change the color and brightness of the LEDs, as well as select from different pre-loaded flashing and fading patterns. The end result, especially with the cloth diffuser, really does look gorgeous. Even if this isn’t the kind of thing you’d wear on a daily basis, we have no doubt that you’ll be getting plenty of attention every time you clip it on.

It should be said that [Stephen] is no stranger to wearable technology. We’ve previously covered his mildly terrifying wrist mounted flamethrower, so if he managed to build that without blowing himself up, we imagine building a light up tie should be a piece of cake in comparison.

Continue reading “Glowtie Is Perfect For Those Fancy Dress Raves”