What do you do when you already have a neat little radio-controlled skid-steer loader? Well, if you’re [ProfessorBoots], you build a neat little dump truck to match!

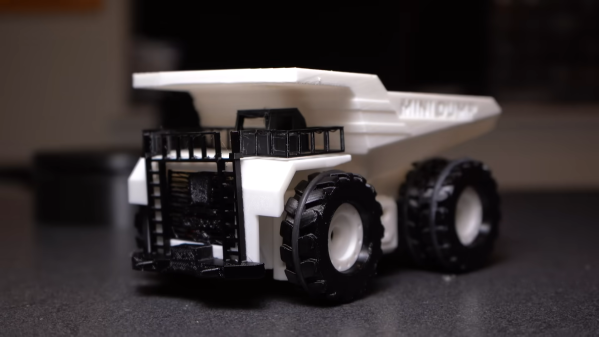

The dump truck is built out of 3D printed components, and has proportions akin to a heavy-duty mining hauler. The dump bed and wheels were oversized relative to the rest of the body to give it a more cartoonish look.

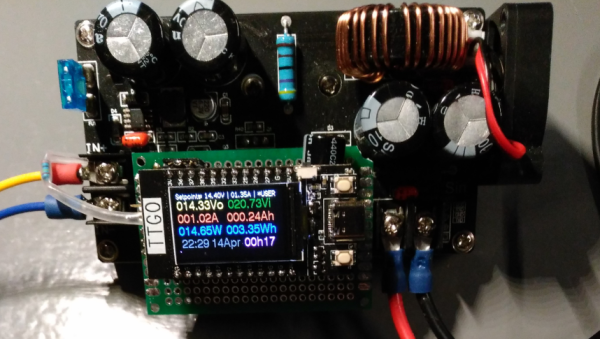

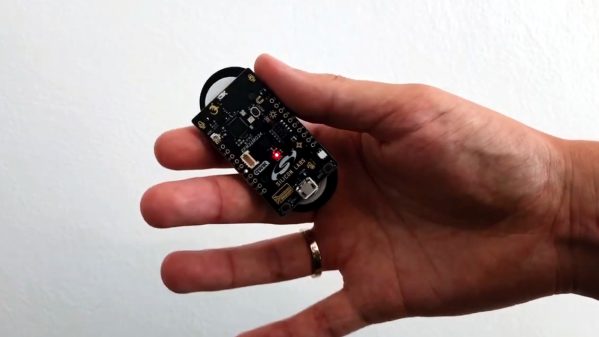

An ESP32 is the brains of the operation. The build is powered by a nifty little 3.6 V rechargeable lithium-ion battery with an integral Micro USB charge port. It’s paired with a boost converter to provide a higher voltage for the servos and motors. Drive is to the rear wheels, thanks to a small DC gear motor. Unlike previous skid-steer designs from [ProfessorBoots], this truck has proper servo-controlled steering. The printed tires are wrapped in rubber o-rings, which is a neat way to make wheels that grip without a lot of fuss. The truck also has a fully-functional dump bed, which looks great fun to play with.

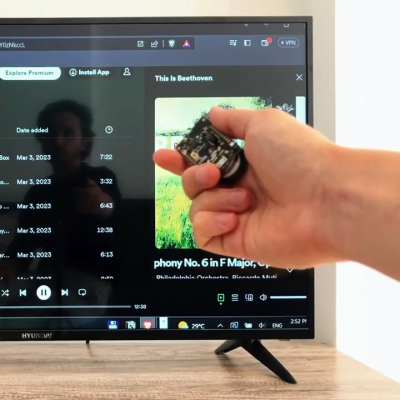

The final build pairs great with the loader that [ProfessorBoots] built previously.

Continue reading “3D Printed Dump Truck Carries Teeny Loads”