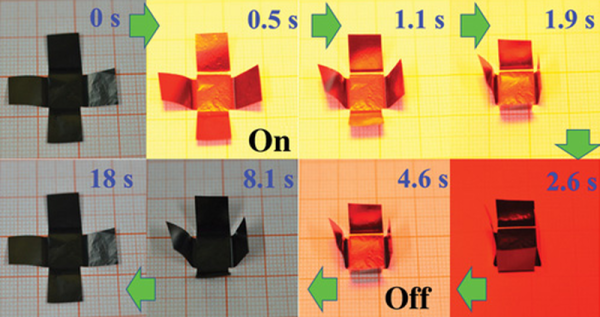

Origami, the art of folding paper into shapes, is the latest craft to fall to automation. Researchers in China have published a paper in Science Advances describing how they created graphene-based paper that can fold itself. According to their paper (that is, the paper they wrote, not their graphene paper), the new material can adopt a predefined shape, walk, or even turn a corner.

Active materials like shape memory polymers, aren’t new. But there are many practical problems with using such materials. Using MGMs (Macroscopic Graphene Materials), the researchers created paper that can change shape based on light. temperature, or humidity.

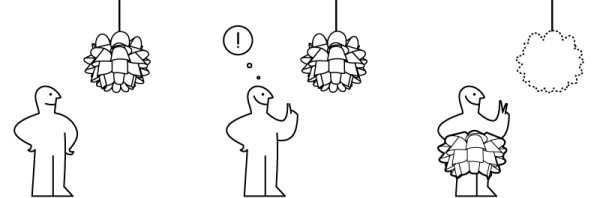

The video below shows a few uses including a self-folding box, a worm-like motion device, and a hand-like piece of paper making a grasping motion. The creators mention that there are a wide range of applications including robotics, artificial muscles, and sensing devices. After watching the video, we couldn’t help but wonder how cool a paper flower that opened in the sunlight would be.

We’ve covered how to make your own graphene in a home lab and even inside a DVD burner. We’ll be interested to see who is the first to hack some graphene paper and what you’ll use it for.