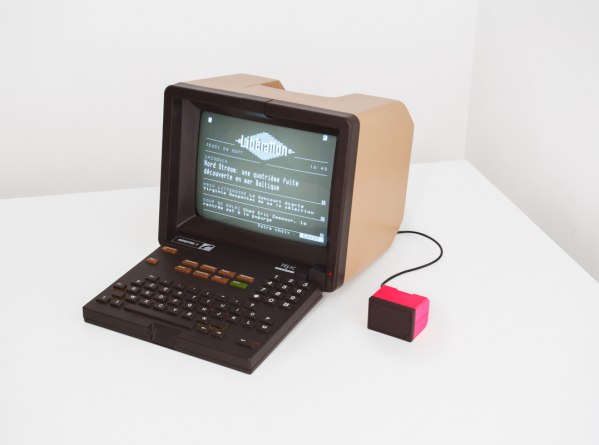

If you didn’t live in France in the 80s or 90s, it’s likely you missed out on one of the most successful computer networks in existence prior to the modern Internet. Known as Minitel, it was an online service available over existing phone lines that offered a connected computer terminal for users to do most things we associate with the modern world, such as booking travel, viewing news, looking up phone numbers, and plenty of other useful activities. While a lot of the original system was never archived, there are still some efforts to restore some of its original functionality like this MiniMit.

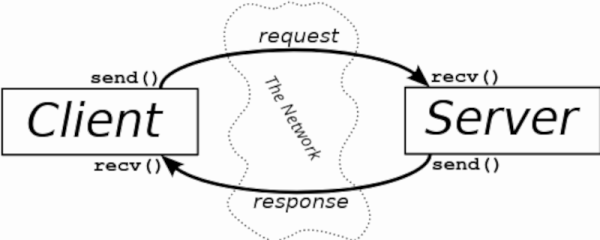

The build requires either an original or a recreation of a Minitel terminal in all its 80s glory, but pairs an ESP32 to support modern network connectivity. The ESP32 interfaces with the Minitel’s DIN socket and provides it with a translation layer between WiFi and the networking type that it would have originally expected to see from the telephone lines. Two of the original developers of Minitel are working on restoring some of the services that would have been available originally as well, which means that the entire system is being redeveloped and not just the original hardware.

We’ve mentioned that this system was first implemented in the 80s, but the surprising thing is that even well after broadband Internet would have been available to most people in France, the Minitel system still had widespread use, not being fully deactivated until 2012. They remain popular as inspiration for other projects as well, like this one which was brought a little more up-to-date with the help of a modern display and Raspberry Pi.