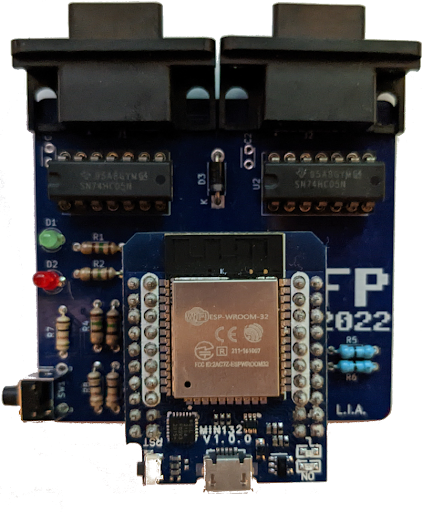

Nothing says “1980s gaming” like a black joystick with a single red fire button. But if you prefer better ergonomics, you can connect modern gamepads to your retrocomputers thanks to a variety of modern-to-classic interface adapters. These typically support just the directional pad and one or two action buttons, leaving out modern features like motion control and haptic feedback.

That’s a bit of a shame, because we think it would be pretty cool to feel that shock in our hands whenever Pitfall Harry drowns in quicksand or Frogger gets hit by traffic. We’re therefore happy to report that [Ricardo Quesada] has decided to add rumble functionality to the Bluetooth-to-Joystick-port interface that he’s been working on. He demonstrates the feature on his Commodore 64 in the video embedded after the break.

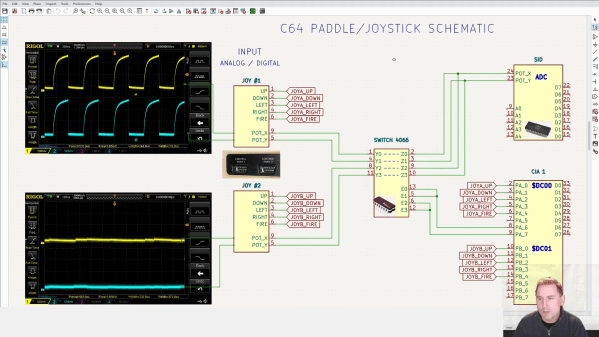

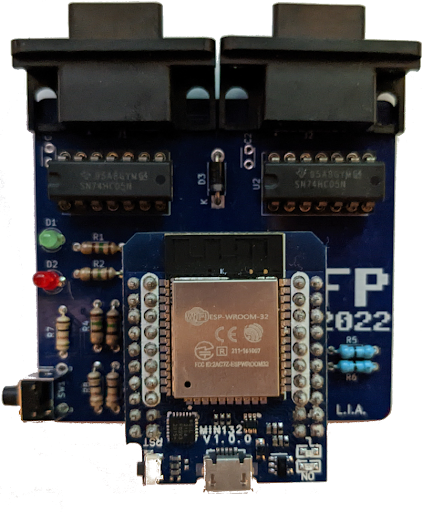

Naturally, any software needs to be adapted to support haptic feedback, but a trickier problem turned out to be the hardware: joystick ports are input-only devices and therefore cannot send “enable rumble” signals to any connected gamepads. [Ricardo] found a clever way around this, using the analog inputs on the joystick port that were typically used for paddle-type controllers.

Naturally, any software needs to be adapted to support haptic feedback, but a trickier problem turned out to be the hardware: joystick ports are input-only devices and therefore cannot send “enable rumble” signals to any connected gamepads. [Ricardo] found a clever way around this, using the analog inputs on the joystick port that were typically used for paddle-type controllers.

The analog-to-digital converter inside the computer works by applying a pulse signal to the analog port and measuring the time it takes to discharge a capacitor. The modern gamepad interface simply detects whether these pulses are present; they can be enabled or disabled through software by toggling the analog readout on the joystick port. This way, the joystick port can be used to send a single bit of information to any device connected to it.

[Ricardo] developed patches for Rambo: First Blood part II and Leman to enable rumble functionality. He describes the process in detail in his blog post, which should enable anyone who knows their way around 6502 machine code to add rumble support to their favorite games.

The adapter works with a variety of retro systems that use the Atari-style joystick interface, but if you’re an Apple II user, you might want to look at this Raspberry Pi-based project that interfaces with its nonstandard joystick interface. If you’re into wireless gaming in general, be sure to also check out our history of wireless game controllers.

Continue reading “Bluetooth Interface Adds Rumble Feedback To Commodore 64 Games” →