There’s a strange synchronicity in the projects we see here at Hackaday, where different people come up with strikingly similar stuff at nearly the same time. We’re not sure why this is, but it’s easily observable, with this vintage altimeter teardown and repair by our good friend [CuriousMarc] as the latest example.

The altimeter that [Marc] dissects in the video below was made by Kollsman, which is what prompted us to recall this recent project that turned a jet engine tachometer into a CPU utilization gauge. That instrument was also manufactured by Kollsman, but was electrically driven. [Marc]’s project required an all-mechanical altimeter, so he ordered a couple from eBay.

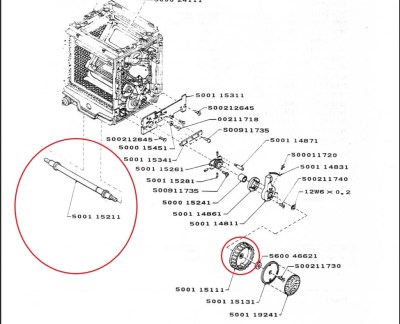

Unfortunately, thanks to rough handling in transit they arrived in less than working condition, necessitating the look inside. For which we’re thankful, of course, because the guts of these aneroid altimeters are quite impressive. The mechanism is all mechanical, with parts that look like something [Click Spring] would make for a fine timepiece. [Marc]’s inspection revealed the problem: a broken pivot screw keeping the expansion and contraction of the aneroid diaphragms from transmitting force to the gear train that moves the needles. The repair was a little improvisational, with 0.5-mm steel balls used to stand in for the borked piece. It may not be flight ready, but it worked well enough to get the instrument back in action.

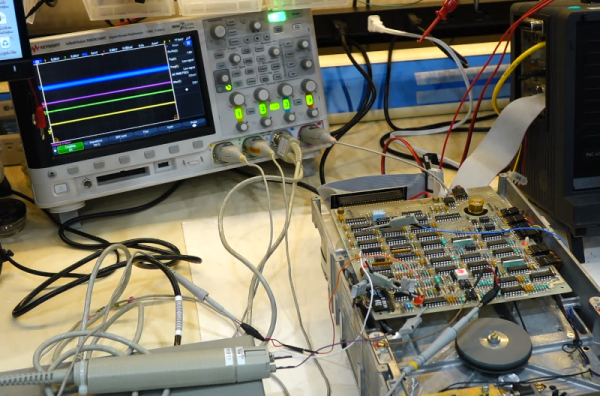

We suspect that [Marc] won’t be able to leave well enough alone on this one, so we’ll be on the lookout for a proper repair. In the meantime, he’ll be able to use this altimeter in the test setup he’s building to test a Bendix air data computer from a 1950s-era jet fighter. Continue reading “A Look Inside A Vintage Aircraft Altimeter”