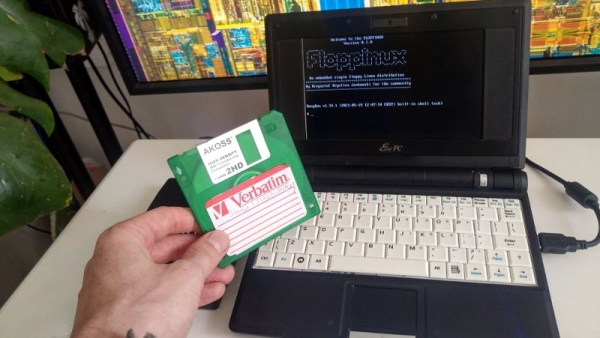

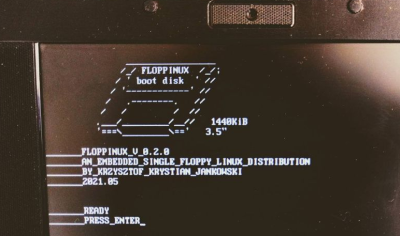

There was a time when booting Linux from a floppy disk was the norm, but of course, those days are long gone. Even if you still had a working 3.5 inch drive, surely the size of the modern kernel alone would far exceed the 1.44 MB capacity of the disks, to say nothing of all the support software required to create a usable operating system. Well that’s what we thought, anyway.

But then [Krzysztof Krystian Jankowski] dropped Floppinux, a live Linux OS that boots from just a single floppy. There’s even a few hundred KB left over on the disk, allowing the user to tuck a few of their own programs and scripts onboard before booting it up. But most impressively, the project doesn’t rely on ancient software releases like so many other embedded systems do. Every component of Floppinux is pulled directly from the cutting edge, including version 5.13.0-rc2 of the Linux kernel which is literally just a few days old.

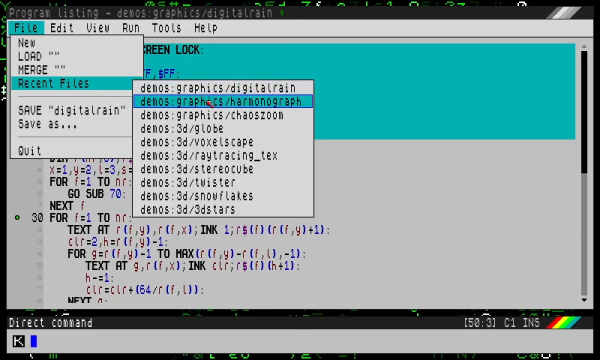

Of course some concessions had to made in order cram the latest Linux kernel and build of BusyBox into slightly north of 1 MB, so Floppinux certainly isn’t what anyone would call a daily driver. The kernel is stripped down the absolute minimum, and is targeted for the decidedly poky i486. [Krzysztof] had to be very selective about which programs actually made the cut as well, so once the system is booted, there’s not a whole lot you can do with it outside of writing some shell scripts. But then, that was sort of the goal to begin with.

If you’re wondering how [Krzysztof] pulled it off, you don’t have to. He walks you though the entire process, down to the commands he used to do everything from pull down and compile the source code to creating the final disk image. Even if you don’t own a floppy drive, it’s well worth following his guide and booting the image up in QEMU just to say you’ve officially built a Linux system from scratch. It’s good for more than just bragging rights; learning how all the components of a minimal install like this fits together will no doubt come in handy the next time you find yourself poking around inside an embedded Linux device.