Retro consoles are great fun, packed with classic games and plenty of nostalgia. However, they also lack the polish and ergonomics of more modern hardware. Serious gamers will often find their original gamepads wearing out, too. A solution to all these problems and more is BlueRetro.

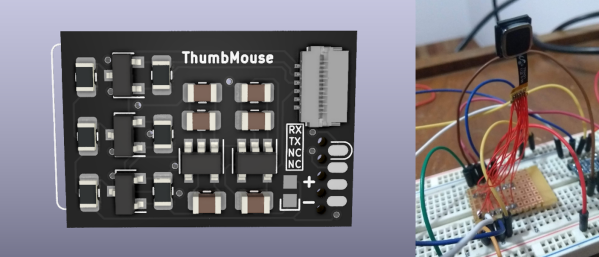

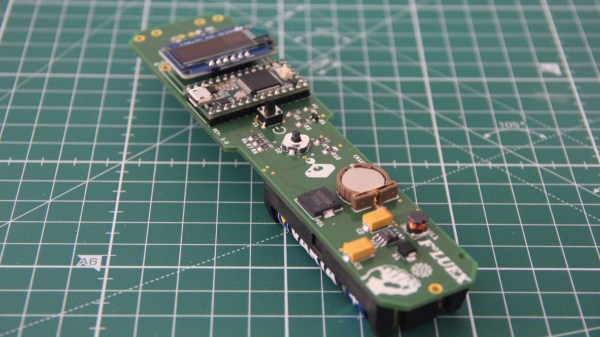

BlueRetro is a Bluetooth controller adapter for a wide variety of vintage console platforms. Developed by [Jacques Gagnon], it uses an ESP32 for its powerful wireless capabilities. One core of the ESP32 is used to speak Bluetooth and handle controller interfacing, while the other processor core handles speaking to the attached console.

The level of attention to detail is where this project really shines. [Jacques] has implemented many advanced features, like mapping axes to buttons and vice versa – essential when swapping controllers across varied systems. The output of BlueRetro is a DB25 connector, which is then used with adapter cabling to hook up to the controller ports of various consoles. It’s even capable of emulating multitap adapters for up to 7-player action.

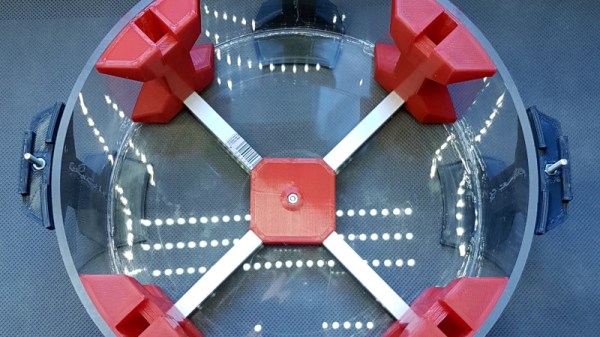

In a video, [Jacques] shows off the hardware in use with his collection of vintage consoles, hooked up on a shelf with an impressive A/V switcher setup. It’s clear that this is the build of a hacker that doesn’t skimp on doing things the right way. We’ve seen his work before too, with a tidy RGB input mod for CRT TVs. Video after the break.

Continue reading “BlueRetro Is The Ultimate Console Controller Adapter”

Automated medical diagnostics is certainly an

Automated medical diagnostics is certainly an