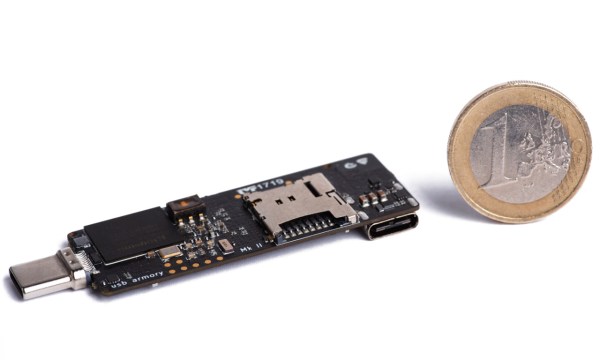

While it might look like a disrobed flash drive or RTL-SDR dongle, the USB Armory Mk II is actually a full-fledged open hardware computer built into the ubiquitous USB “stick” format. But more than just that, it’s optimized for security research and boasts a list of features that are sure to get the attention of any pentesters in the audience. Fine tuned thanks to the feedback developer [Inverse Path] received about the original version of the hardware, the Mk II promises to be the last word in secure mobile computing.

Compared to the original hardware, the most obvious change is the switch to USB-C. The previous USB Armory used traces on the PCB to plug directly into a USB Type-A port, but this time around [Inverse Path] has put a proper male connector on the front of the board. Nominally, the USB Armory is plugged into a host computer to provide it with power and a network connection, though it also has the ability to disguise itself as a storage or input device for more stealthy applications. There’s also a female USB-C port on the Mk II, which can be used to connect additional devices, a feature the previous version lacked.

The USB Armory Mk II is powered by an upgraded 900 MHz ARM Cortex-A7 processor, though it retains the same 512 MB of RAM from the previous version. Like the original, there’s a micro SD slot to hold the Linux operating system, but this time it’s supplemented with an onboard 16 GB eMMC chip. There’s even a physical switch that allows the user to choose which storage device they want to boot from. Other additions for the Mk II include Bluetooth connectivity, and a hardware true random number generator (TRNG).

The USB Armory Mk II is powered by an upgraded 900 MHz ARM Cortex-A7 processor, though it retains the same 512 MB of RAM from the previous version. Like the original, there’s a micro SD slot to hold the Linux operating system, but this time it’s supplemented with an onboard 16 GB eMMC chip. There’s even a physical switch that allows the user to choose which storage device they want to boot from. Other additions for the Mk II include Bluetooth connectivity, and a hardware true random number generator (TRNG).

We first brought you word of the original USB Armory back in 2014, and it’s always good to see an open hardware project thriving and iterating years later. While the $149 price tag arguably puts the MKII out of the tinkering budget for many of us, there’s clearly a market for niche devices like this and we can’t wait to see what [Inverse Path] comes up with next.

The USB Armory Mk II is powered by an upgraded 900 MHz ARM Cortex-A7 processor, though it retains the same 512 MB of RAM from the previous version. Like the original, there’s a micro SD slot to hold the Linux operating system, but this time it’s supplemented with an onboard 16 GB eMMC chip. There’s even a physical switch that allows the user to choose which storage device they want to boot from. Other additions for the Mk II include Bluetooth connectivity, and a hardware true random number generator (TRNG).

The USB Armory Mk II is powered by an upgraded 900 MHz ARM Cortex-A7 processor, though it retains the same 512 MB of RAM from the previous version. Like the original, there’s a micro SD slot to hold the Linux operating system, but this time it’s supplemented with an onboard 16 GB eMMC chip. There’s even a physical switch that allows the user to choose which storage device they want to boot from. Other additions for the Mk II include Bluetooth connectivity, and a hardware true random number generator (TRNG).