At one time or another, we’ve all suffered through working with a piece of equipment that didn’t feature a way to export its data to another device. Whether it was just too old to offer such niceties, or the manufacturer locked the capability behind some upgrade, the pain of staring at digits ticking over on a glowing LCD display and wishing there was a practical way to scrape what our eyes were seeing is well known to hackers.

That was precisely the inspiration for DoMSnif, the dot matrix LCD sniffer that [Blecky] has been working on. Originally the project started as a way to record the temperature of his BRTRO-420 reflow oven, but realizing that such a device could have widespread appeal to other hardware hackers, he’s rightfully decided to enter it into the 2019 Hackaday Prize. If perfected, it could be an excellent way to bolt data capture capabilities to your older devices.

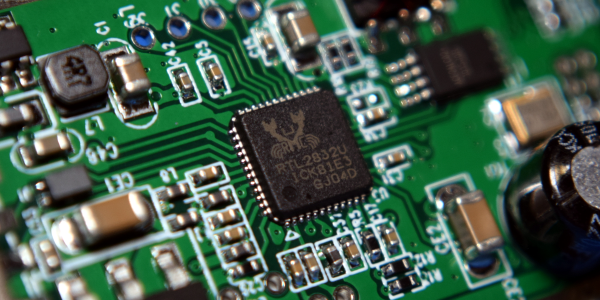

The first phase of this project was figuring out how to capture and parse the signals going into the device’s KS0108 LCD. Getting the data was certainly easy enough, he just had to hook a logic analyzer up between the display and the main board of the device. Of course, figuring out what it all means is a different story.

The first phase of this project was figuring out how to capture and parse the signals going into the device’s KS0108 LCD. Getting the data was certainly easy enough, he just had to hook a logic analyzer up between the display and the main board of the device. Of course, figuring out what it all means is a different story.

After running the oven for a bit with the analyzer recording, [Blecky] had more than enough data to get started on decoding it. Luckily, the layout of this fairly common 128×64 pixel display is well documented and easy enough to understand. With a little work, he was able to create a tool that would import the captured data and display it on a virtual LCD.

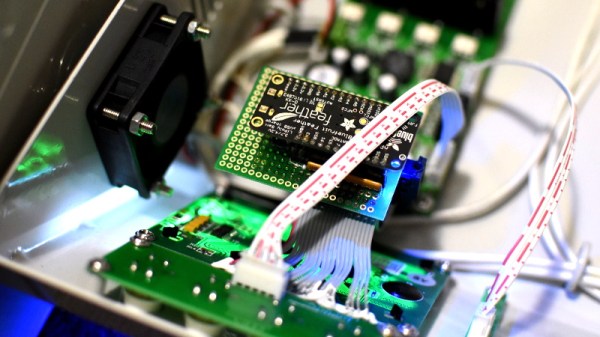

Unfortunately, the Bluetooth part is where things get tricky. Ultimately, [Blecky] wants to ditch the logic analyzer and use a Adafruit Feather nRF52 Bluefruit to capture the signals going to the LCD and pipe them to a waiting device over Bluetooth. But his testing has found that the nRF52’s radio is simply too slow. The display is receiving data every 14us, but it takes the radio at least 50us to send a packet.

[Blecky] is looking at ways around this problem, and we’re confident he’ll crack it. The solution could be in buffering and compressing the data before sending it out, though you’d lose the ability to monitor the display in real-time. Even if he has to abandon the Bluetooth aspect entirely and make the device wired, we still think there would be a market for an easy to use hardware and software solution for scraping LCD data.