[Joey] was about to desolder something when the unthinkable happened: his iconic blue anodized aluminium desoldering pump was nowhere to be found. Months before, having burned himself on copper braid, he’d sworn off the stuff and sold it all for scrap. He scratched uselessly at a solder joint with a fingernail and thought to himself: if only I’d used the scrap proceeds to buy a backup desoldering pump.

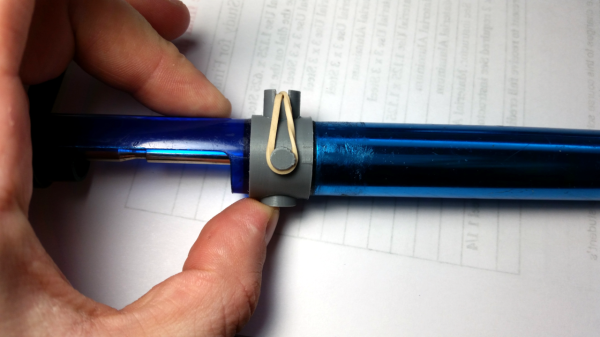

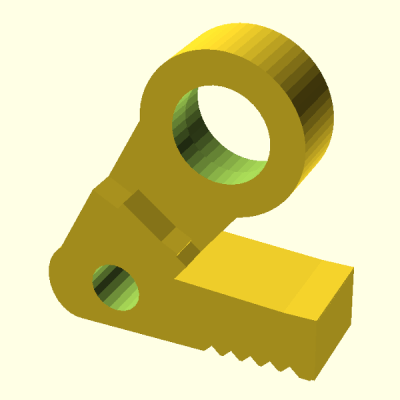

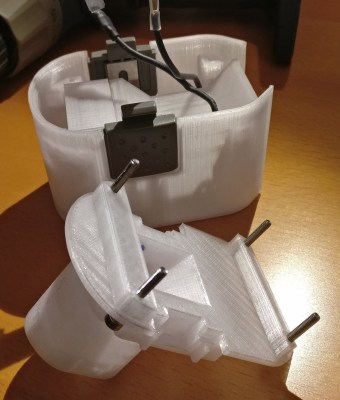

Determined to desolder by any means necessary, [Joey] dove into his junk bin and emerged carrying an old pump with a broken button. He’d heard all about our Repairs You Can Print contest and got to work designing a replacement in two parts. The new button goes all the way through the pump and is held in check with a rubber band, which sits in a groove on the back side. The second piece is a collar with a pair of ears that fits around the tube and anchors the button and the rubber band. It’s working well so far, and you can see it suck in real-time after the break.

We’re not sure what will happen when the rubber band fails. If [Joey] doesn’t have another, maybe he can print a new one out of Ninjaflex, or build his own desoldering station. Or maybe he’ll turn to the fire and tweezers method.

Continue reading “Repairs You Can Print: 3D Printing Is For (Solder) Suckers”

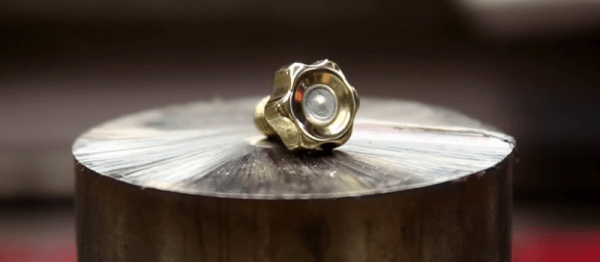

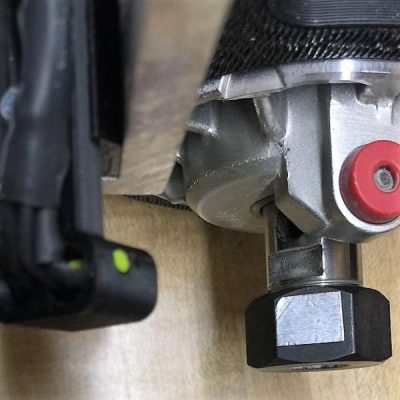

The CNC router in question is the popular Sienci, and the 3D-printed brackets for the photodiode and LED are somewhat specific for that machine. But [tmbarbour] has included STL files in his exhaustively detailed write-up, so modifying them to fit another machine should be easy. The sensor hangs down just far enough to watch a reflector on one of the flats of the collet nut; we’d worry about the reflector surviving tool changes, but it’s just a piece of shiny tape that’s easily replaced. The sensor feeds into a DIO pin on a Nano, and a small OLED display shows a digital readout along with an analog gauge. The display update speed is decent — not too laggy. Impressive build overall, and we like the idea of using a piece of PLA filament as a rivet to hold the diodes into the sensor arm.

The CNC router in question is the popular Sienci, and the 3D-printed brackets for the photodiode and LED are somewhat specific for that machine. But [tmbarbour] has included STL files in his exhaustively detailed write-up, so modifying them to fit another machine should be easy. The sensor hangs down just far enough to watch a reflector on one of the flats of the collet nut; we’d worry about the reflector surviving tool changes, but it’s just a piece of shiny tape that’s easily replaced. The sensor feeds into a DIO pin on a Nano, and a small OLED display shows a digital readout along with an analog gauge. The display update speed is decent — not too laggy. Impressive build overall, and we like the idea of using a piece of PLA filament as a rivet to hold the diodes into the sensor arm.