It wouldn’t be much of a stretch to assume that anyone reading Hackaday regularly has at least progressed to the point where they can connect an LED to a microcontroller and get it to blink without setting anything on fire. We won’t even chastise you for not doing it with a 555 timer. It’s also not a stretch to say if you can successfully put together the “Hello World” of modern electronics on a breadboard, you’re well on the way to adding a few more LEDs, some sensors, and a couple buttons to that microcontroller and producing something that might come dangerously close to a useful gadget. Hardware hacking sneaks up on you like that.

Here’s where it gets tricky: how many of us are still stuck at that point? Don’t be shy, there’s no shame in it. A large chunk of the “completed” projects that grace these pages are still on breadboards, and if we had to pass on every project that still had a full-on development board like the Arduino or Wemos D1 at its heart…well, let’s just say it wouldn’t be pretty.

Of course, if you’re just building something as a personal project, there’s often little advantage to having a PCB spun up or building a custom enclosure. But what happens when you want to build more than one? If you’ve got an idea worth putting into production, you’ve got to approach the problem with a bit more finesse. Especially if you’re looking to turn a profit on the venture.

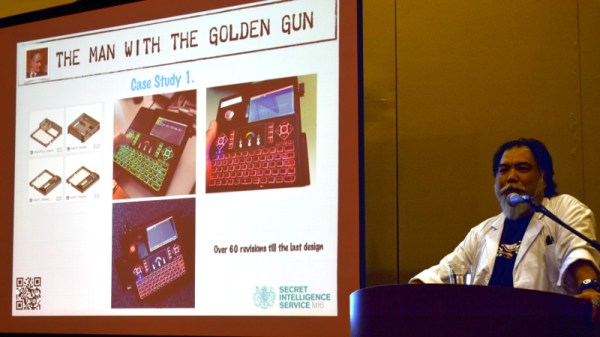

At the recent WOPR Summit in Atlantic City, there were a pair of presentations which dealt specifically with taking your hardware designs to the next level. Russell Handorf and Mike Kershaw hosted an epic four hour workshop called Strategies for your Projects: Concept to Prototype and El Kentaro gave a fascinating talk about his design process called Being Q: Designing Hacking Gadgets which together tackled both the practical and somewhat more philosophical aspects of building hardware for an audience larger than just yourself.