The amateur radio community often gets stereotyped as a hobby with a minimum age requirement around 70, gatekeeping airwaves from those with less experience or simply ignoring unfamiliar beginners. While there is a small amount of truth to this on some local repeaters or specific frequencies, the spectrum is big enough to easily ignore those types and explore the hobby without worry (provided you are properly licensed). One of the best examples of this we’ve seen recently of esoteric radio use is this method of using packet radio to play a game of Colossal Cave Adventure.

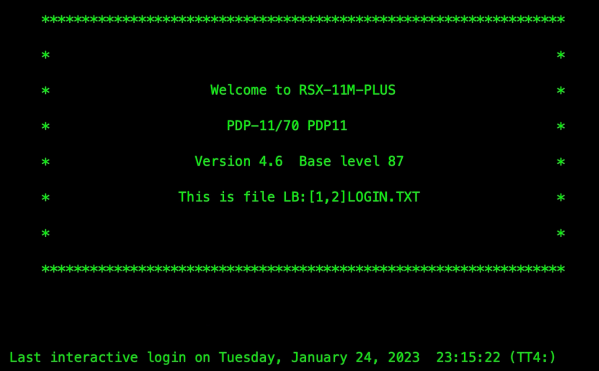

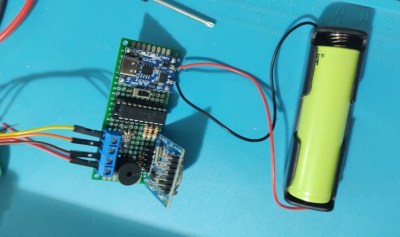

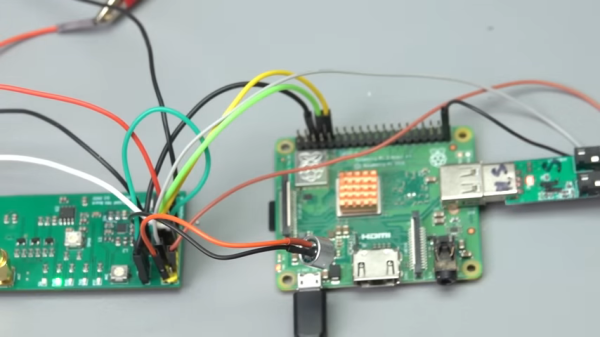

Packet radio is a method by which digital information can be sent out over the air to nodes, which are programmed to receive these transmissions and act on them. Typically this involves something like email or SMS messaging, so playing a text-based game over the air is not too much different than its intended use. For this build, [GlassTTY] aka [G6AML] is using a Kenwood TH-D72 which receives the packets from a Mac computer. It broadcasts these packets to his node, which receives these packets and sends them to a PDP-11 running the game. Information is then sent back to the Kenwood and attached Mac in much the same way as a standard Internet connection.

The unique features of packet radio make it both an interesting and useful niche within the ham radio community, allowing for all kinds of uses where data transmission might otherwise be infeasible or impossible. A common use case is APRS, which is often used on VHF bands to send weather and position information out, but there are plenty of other uses for it as well.