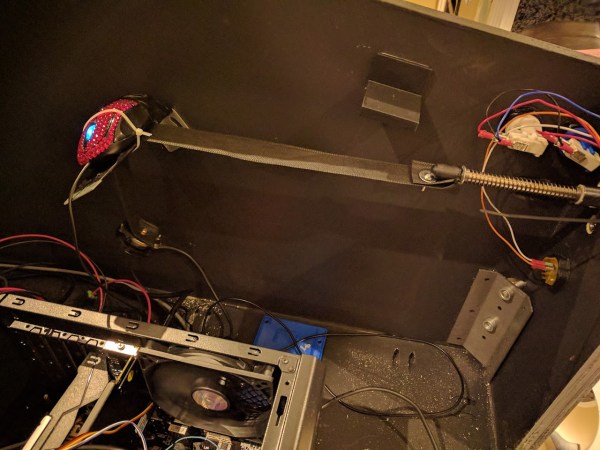

While we might all be quick to grab a microcontroller and an appropriate sensor to solve some problem, gather data about a system, or control another piece of technology, there are some downsides with this method. Software has a lot of failure modes, and relying on it without any backups or redundancy can lead to problems. Often, a much more reliable way to solve a simple problem is with hardware. This heating circuit, for example, uses a MOSFET as a heating element and as its own temperature control.

The function of the circuit relies on a parasitic diode formed within the transistor itself, inherent in its construction. This diode is found in most power MOSFETs and conducts from the source to the drain. The key is that it conducts at a rate proportional to its temperature, so if the circuit is fed with AC, during the negative half of the voltage cycle this diode can be probed and used as a thermostat. In this build, it is controlled by a set of resistors attached to a voltage regulator, which turn the heater on if it hasn’t reached its threshold temperature yet.

In theory, these resistors could be replaced with potentiometers to allow for adjustable heat for certain applications, with plastic cutting and welding, temperature control for small biological systems, or heating other circuits as target applications for this type of analog circuitry. For more analog circuit design inspiration, though, you’ll want to take a look at some classic pieces of electronics literature.