When we see an extremely DIY project, you always get someone who jokes “well, you didn’t collect sand and grow your own silicon”. [Patrícia J. Reis] and [Stefanie Wuschitz] did the next best thing: they collected local soil, sieved it down, and fired their own clay PCB substrates over a campfire. They even built up a portable lab-in-a-backpack so they could go from dirt to blinky in the woods with just what they carried on their back.

This project is half art, half extreme DIY practice, and half environmental consciousness. (There’s overlap.) And the clay PCB is just part of the equation. In an effort to approach zero-impact electronics, they pulled ATmega328s out of broken Arduino boards, and otherwise “urban mined” everything else they could: desoldering components from the junk bin along the way.

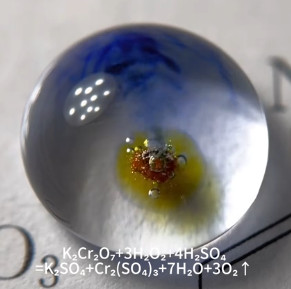

The traces themselves turned out to be the tricky bit. They are embossed with a 3D print into the clay and then filled with silver before firing. The pair experimented with a variety of the obvious metals, and silver was the only candidate that was both conductive and could be soldered to after firing. Where did they get the silver dust? They bought silver paint from a local supplier who makes it out of waste dust from a jewelry factory. We suppose they could have sat around the campfire with some old silver spoons and a file, but you have to draw the line somewhere. These are clay PCBs, people!

Is this practical? Nope! It’s an experiment to see how far they can take the idea of the pre-industrial, or maybe post-apocalyptic, Arduino. [Patrícia] mentions that the firing is particularly unreliable, and variations in thickness and firing temperature lead to many cracks. It’s an art that takes experience to master.

We actually got to see the working demos in the flesh, and can confirm that they did indeed blink! Plus, they look super cool. The video from their talk is heavy on theory, but we love the practice.

DIY clay PCBs make our own toner transfer techniques look like something out of the Jetsons.