It seems like within the last ten years, every other gadget to be released has some sort of heart rate monitoring capability. Most modern smartwatches can report your BPMs, and we’ve even seen some headphones with the same ability hitting the market. Most of these devices use an optical measurement method in which skin is illuminated (usually by an LED) and a sensor records changes in skin color and light absorption. This method is called Photoplethysmography (PPG), and has even been implemented (in a simple form) in smartphone apps in which the data is generated by video of your finger covering the phone camera.

The basic theory of operation here has its roots in an experiment you probably undertook as a child. Did you ever hold a flashlight up to your hand to see the light, filtered red by your blood, shine through? That’s exactly what’s happening here. One key detail that is hard to perceive when a flashlight is illuminating your entire hand, however, is that deoxygenated blood is darker in color than oxygenated blood. By observing the frequency of the light-dark color change, we can back out the heart rate.

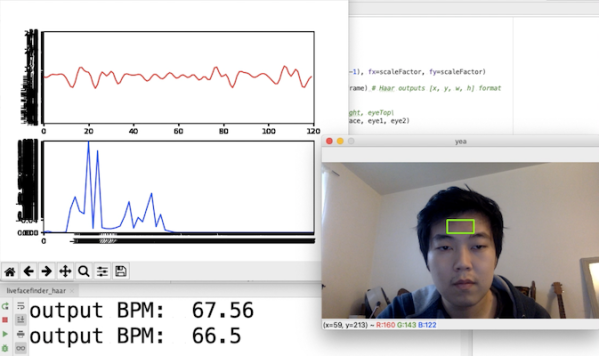

This is exactly how [Andy Kong] approached two methods of measuring heart rate from a webcam.

Method 1: The Cover-Up

The first detection scheme [Andy] tried is what he refers to as the “phone flashlight trick”. Essentially, you cover the webcam lens entirely with your finger. Ambient light shines through your skin and produces a video stream that looks like a dark red rectangle. Though it may be imperceptible to us, the color changes ever-so-slightly as your heart beats. An FFT of the raw data gives us a heart rate that’s surprisingly accurate. [Andy] even has a live demo up that you can try for yourself (just remember to clean the smudges off your webcam afterwards).

Method 2: Remote Sensing

Now things are getting a bit more advanced. What if you don’t want to clean your webcam after each time you measure your heart rate? Well thankfully there’s a remote sensing option as well.

For this method, [Andy] is actually using OpenCV to measure the cyclical swelling and shrinking of blood vessels in your skin by measuring the color change in your face. It’s absolutely mind-blowing that this works, considering the resolution of a standard webcam. He found the most success by focusing on fleshy patches of skin right below the eyes, though he says others recommend taking a look at the forehead.

Every now and then we see something that works even though it really seems like it shouldn’t. How is a webcam sensitive enough to measure these minute changes in facial color? Why isn’t the signal uselessly noisy? This project is in good company with other neat heart rate measurement tricks we’ve seen. It’s amazing that this works at all, and even more incredible that it works so well.