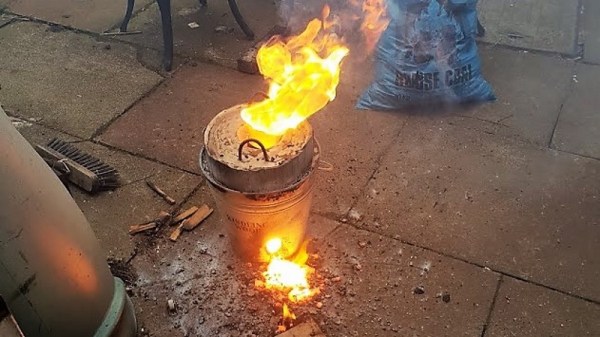

Every now and then in histories of the 20th’s century’s earlier years, you will see pictures of cars and commercial vehicles equipped with bulky drums, contraptions to make their fuel from waste wood. These are portable gas generators known as gasifiers, and to show how they work there’s [Greenhill Forge] with a build video.

When you burn a piece of wood, you expect to see flame. But what you are looking at in that flame are the gaseous products of the wood breaking down under the heat of combustion. The gasifier carefully regulates a burn to avoid that final flame, with the flammable gasses instead being drawn off for use as fuel.

The chemistry is straightforward enough, with exothermic combustion producing heat, water vapour, and carbon dioxide, before a further endothermic reduction stage produces carbon monoxide and hydrogen. He’s running his system from charcoal which is close to pure carbon presumably to avoid dealing with tar, and at this stage he’s not adding any steam, so we’re a little mystified as to where the hydrogen comes from unless there is enough water vapour in the air.

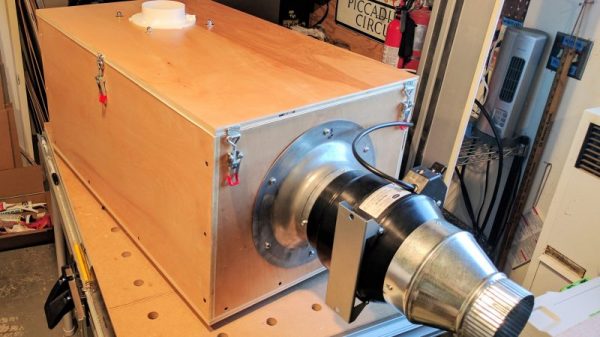

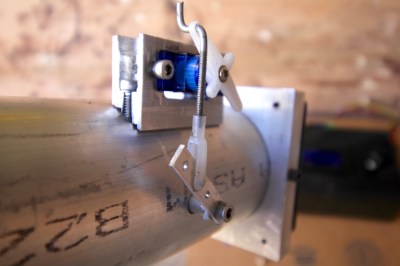

His retort is fabricated from sheets steel, and is followed by a cyclone and a filter drum to remove particulates from the gas. It relies on a forced air draft from a fan or a small internal combustion engine, and we’re surprised both how quickly it ignites and how relatively low a temperature the output gas settles at. The engine runs with a surprisingly simple gas mixer in place of a carburetor, and seems to be quite smooth in operation.

This is one of those devices that has fascinated us for a long time, and we’re grateful for the chance to see it up close. The video is below the break, and we’re promised a series of follow-ups as the design is refined.

Continue reading “Keep That Engine Running, With A Gassifier”

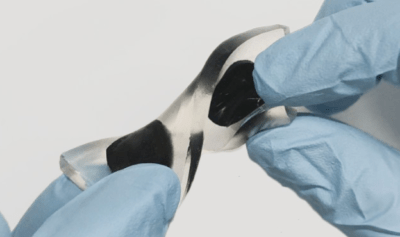

their lifespan. While the concept of food-based robots may seem unusual, the potential applications in medicine and reducing waste during food delivery are significant driving factors behind this idea.

their lifespan. While the concept of food-based robots may seem unusual, the potential applications in medicine and reducing waste during food delivery are significant driving factors behind this idea. activated charcoal (AC) electrodes on a gelatin substrate. Water is split into its constituent oxygen and hydrogen by applying a voltage to the structure. These gasses adsorb into the AC surface and later recombine back into the water, providing a usable one-volt output for ten minutes with a similar charge time. This simple structure is reusable and, once expired, dissolves harmlessly in (simulated) gastric fluid in twenty minutes. Such a device could potentially power a GI-tract exploratory robot or other sensor devices.

activated charcoal (AC) electrodes on a gelatin substrate. Water is split into its constituent oxygen and hydrogen by applying a voltage to the structure. These gasses adsorb into the AC surface and later recombine back into the water, providing a usable one-volt output for ten minutes with a similar charge time. This simple structure is reusable and, once expired, dissolves harmlessly in (simulated) gastric fluid in twenty minutes. Such a device could potentially power a GI-tract exploratory robot or other sensor devices.

This began by collecting 150 pounds (!) of magnetic dirt from dry lake beds while hiking using a magnet pickup tool with release lever that he got from Harbor Freight. Several repeated magnetic refining passes separated the black ore from non-metallic sands ready for the furnace that he built. That is used to fire up the raw materials using 150 pounds of charcoal, changing the chemical composition by adding carbon and resulting in a gnarly lump of iron

This began by collecting 150 pounds (!) of magnetic dirt from dry lake beds while hiking using a magnet pickup tool with release lever that he got from Harbor Freight. Several repeated magnetic refining passes separated the black ore from non-metallic sands ready for the furnace that he built. That is used to fire up the raw materials using 150 pounds of charcoal, changing the chemical composition by adding carbon and resulting in a gnarly lump of iron