Sometimes you get plain lucky in multiple ways, enabling you to complete a hack that would otherwise have seemed improbable. [Mario Nagano] managed to attach a vintage 1950’s lens to a modern mirrorless camera (translated from Portuguese).

Photographers tend to collect a lot of gear and [Mario] is no exception. At a local fair in Sao Paolo, he managed to pick up a Voigtlander Bessa I – a bellows camera (or folding camera). It came cheap, and the seller warned him as much, commenting on the bad external shape it was in. But [Mario] had a sharp eye, and noticed that this was a camera that would have remained closed most of the time, due to its construction.

Inspection showed that the bellows was intact. What excited and surprised him was the excellent Color-Skopar objective mounted on a Prontor-S trigger, which is considered premium compared to the entry level Vaskar lens. His plan was to pick up another Voigtlander Bessa-I with a better preserved body, but the cheaper lens and do a simple swap. He never did find another replacement though. Instead, he decided to fix the excellent vintage lens to a DSLR body.

He’d read about a few other similar hacks, but they all involved a lot of complicated adapters which was beyond his skills. Removing the lens from the vintage camera was straightforward. It was held to the body by a simple threaded ring nut and could not only be removed easily, but the operation was reversible and didn’t cause any damage to the old camera body. The vintage lens has a 31.5mm mounting thread while his Olympus DSLR body had a standard 42mm thread. Fabricating a custom adapter from scratch would have cost him a lot in terms of time and money. That’s when he got lucky again. He had recently purchased a Fotodiox Spotmatic camera body cap. It’s made of aluminium and just needed a hole bored through its center to match the vintage lens. There’s no dearth of machine shops in Sao Paolo and it took him a few bucks to get it accurately machined. The new adapter could now be easily fixed to the old lens using the original 31.5mm ring nut.

The lens has a 105mm focal length, so the final assembly must ensure that this distance is maintained. And he got lucky once again. He managed to dig up a VEB Pentacom M42 macro bellows from an old damaged camera. Was it worth all the effort ? Take a look at these pictures here, here and here.

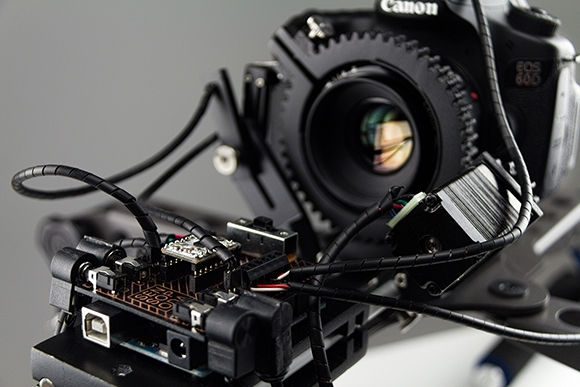

Once the Pi was outfitted with a 3G modem, [madis] can log in and change the camera settings from anywhere. It’s normally set up to take a picture once every fifteen minutes, but ONLY during working hours. Presumably this saves a bunch of video editing later whereas a normal timelapse camera would require cutting out a bunch of nights and weekends.

Once the Pi was outfitted with a 3G modem, [madis] can log in and change the camera settings from anywhere. It’s normally set up to take a picture once every fifteen minutes, but ONLY during working hours. Presumably this saves a bunch of video editing later whereas a normal timelapse camera would require cutting out a bunch of nights and weekends.