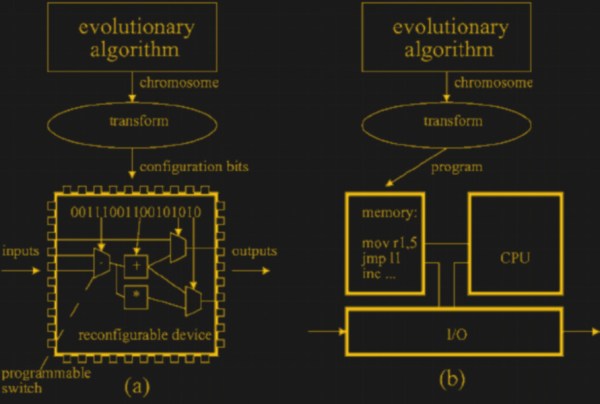

When the only tool you have is a hammer, all problems look like nails. And if your goal is to emulate the behavior of an FPGA but your only tools are FPGAs, then your nail-and-hammer issue starts getting a little bit interesting. That’s at least what a group of students at Cornell recently found when learning about the Xilinx FPGA used by a researcher in the 1990s by programming its functionality into another FPGA.

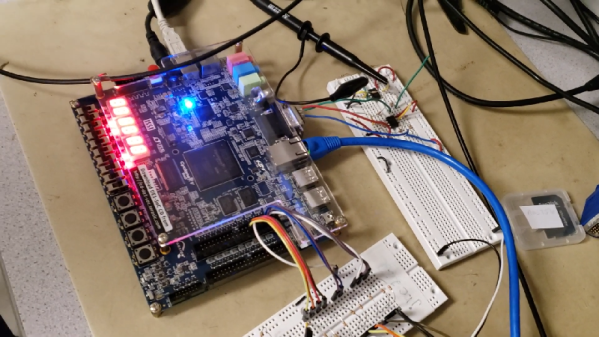

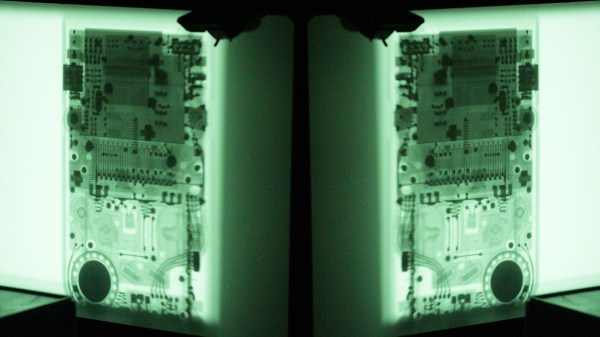

Using outdated hardware to recreate a technical paper from decades ago might be possible, but an easier solution was simply to emulate the Xilinx in a more modern FPGA, the Cyclone V FPGA from Terasic. This allows much easier manipulation of I/O as well as reducing the hassle required to reprogram the device. Once all of that was set up, it was much simpler to perform the desired task originally set up in that 90s paper: using evolutionary algorithms to discriminate between different inputs.

While we will leave the investigation into the algorithms and the I/O used in this project as an academic exercise for the reader, this does serve as a good reminder that we don’t always have to have the exact hardware on hand to get the job done. Old computers can be duplicated on less expensive, more modern equipment, and of course video games from days of yore are a snap to play on other hardware now too.

Thanks to [Bruce Land] for the tip!