We often think that not enough people are building things with FPGAs. We also love the retrotechtacular posts on old computer hardware. So it was hard to pass up [karlwoodward’s] post about the Chip Hack EDSAC Challenge — part of the 2017 Wuthering Bytes festival.

You might recognize EDSAC as what was arguably the first operational computer if you define a computer as what we think of today as a computer. [Maurice Wilkes] and his team invented a lot of things we take for granted today including subroutines (Wheeler jumps named after a graduate student).

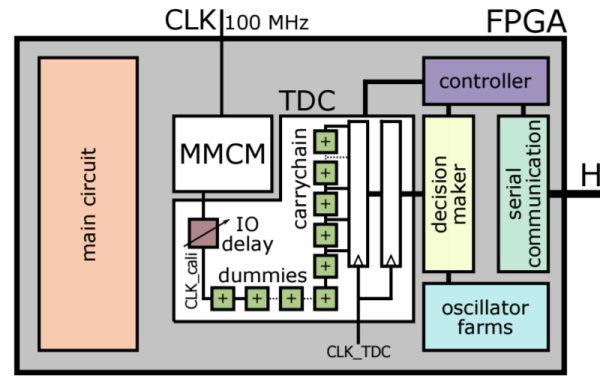

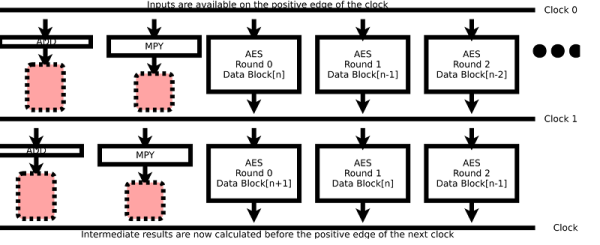

The point to the EDSAC challenge was to expose people to creating designs with FPGAs, particularly using the Verilog hardware description language (HDL). If you want to follow along or run your own Chip Hack, the materials are available on the Web. You can see an FPGA driving a tape punch to create souvenir tapes in the video, below.

Some of the exercises are pretty simple and that’s perfect if you are starting out. The challenge uses a board with a Lattice ice40 FPGA and the open source toolchain for Lattice we’ve covered before. In fact, we’ve even done our own tutorials on the same basic device (but not the same board). Our final project generated PWM, not paper tape.

For the record, EDSAC was awesome. The execution unit was serial and processed bits that marched in one at a time over a mercury delay line. There is quite a bit of documentation and even some simulators, so if you ever wanted to get your hands into an old computer, this one isn’t a bad one to try.

Continue reading “Learn FPGA Programming From The 1940s” →