If you’ve ever attended a hacker camp, you’ll know the problem of a field of tents lit only by the glow of laser illumination through the haze and set to the distant thump of electronic dance music. You need to complete that project, but the sun’s gone down and you didn’t have space in your pack to bring a floodlight.

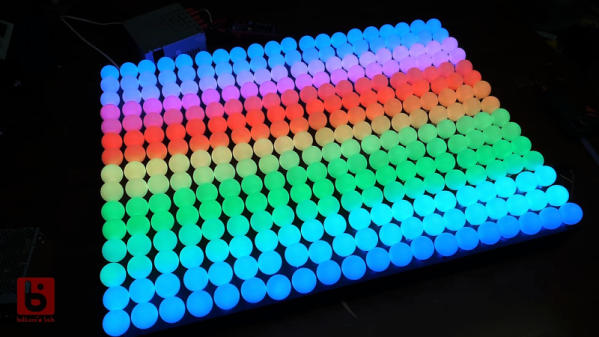

In Days of Yore you might have stuck a flickering candle in an empty Club-Mate bottle and carried on, but this is the 21st century. [Jana Marie] has the solution for you, and instead of a candle, her Club-Mate bottle is topped a stack of LED-adorned PCBs with a lithium-ion battery providing a high intensity downlight. It’s more than just a simple light though, it features variable brightness and colour temperature through touch controls on the top surface, as well as the ability to charge extra 18650 cells. At its heart is an STM32F334 microcontroller with a nifty use of its onboard timer to drive a boost converter, and power input is via USB-C.

We first saw an early take on this project providing illumination for a bit of after-dark Hacky Racer fettling at last year’s EMF 2018 hacker camp, since then it has seen some revisions. It’s all open-source so you can give it a go yourself if you like it.