When it comes to cordless power tools, color is an important brand selection criterion. There’s Milwaukee red, for the rich people, the black and yellow of DeWalt, and Makita has a sort of teal thing going on. But when you see that painful shade of fluorescent green, you know you’ve got one of the wide range of bargain tools and accessories that only Ryobi can offer.

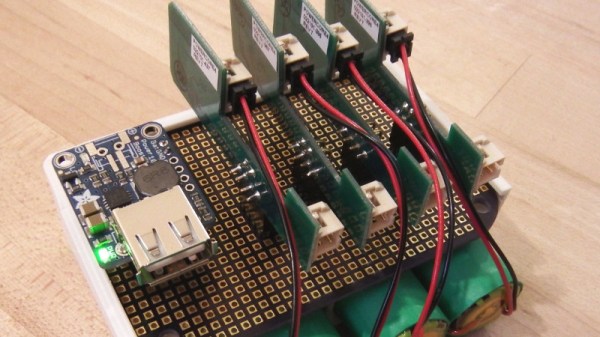

Like many of us, Redditor [Grunthos503] had a few junked Ryobi tools lying about, and managed to cobble together this battery-powered inverter for light-duty applications. The build started with a broken Ryobi charger, whose main feature was a fairly large case once relieved of its defunct guts, plus an existing socket for 18-volt battery packs. Added to that was a small Ryobi inverter, which normally plugs into the Ryobi battery pack and converts the 18 VDC to 120 VAC. Sadly, though, the inverter fan is loud, and the battery socket is sketchy. But with a little case modding and a liberal amount of hot glue, the inverter found a new home inside the charger case, with a new, quieter fan and even an XT60 connector for non-brand batteries.

It’s a simple hack, but one that [Grunthos503] may really need someday, as it’s intended to run a CPAP machine in case of a power outage — hence the need for a fan that’s quiet enough to sleep with. And it’s a pretty good hack — we honestly had to look twice to see what was done here. Maybe it was just the green plastic dazzling us. Although maybe we’re too hard on Ryobi — after all, they are pretty hackable.

Thanks to [Risu no Kairu] for the tip on this one.