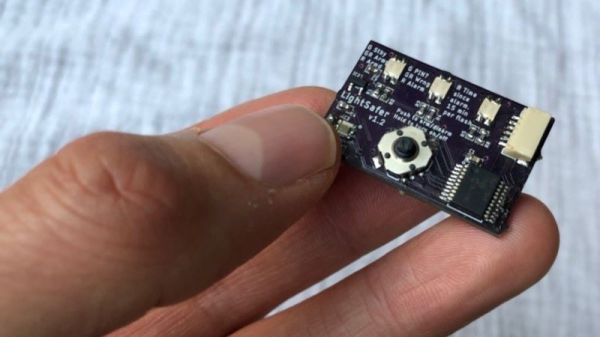

As things get smaller, we can fit more processing power into devices like robots to allow them to do more things or interact with their environment in new ways. If not, we can at least build them for less cost. But the design process can get exponentially more complicated when miniaturizing things. [Carl] wanted to build the smallest 9-axis robotic microcontroller with as many features as possible, and went through a number of design iterations to finally get to this extremely small robotics platform.

Although there are smaller wireless-enabled microcontrollers, [Carl] based this project around the popular ESP32 platform to allow it to be usable by a wider range of people. With that module taking up most of the top side of the PCB, he turned to the bottom to add the rest of the components for the platform. The first thing to add was a power management circuit, and after one iteration he settled on a circuit which can provide the board power from a battery or a USB cable, while also managing the battery’s charge. As for sensors, it has a light sensor and an optional 9-axis motion sensor, allowing for gesture sensing, proximity detection, and motion tracking.

Of course there were some compromises in this design to minimize the footprint, like placing the antenna near the USB-C charger and sacrificing some processing power compared to other development boards like the STM-32. But for the size and cost of components it’s hard to get so many features in such a small package. [Carl] is using it to build some pretty tiny robots so it suits his needs perfectly. In fact, it’s hard to find anything smaller that isn’t a bristlebot.

Continue reading “The Design Process For A Tiny Robot Brain”

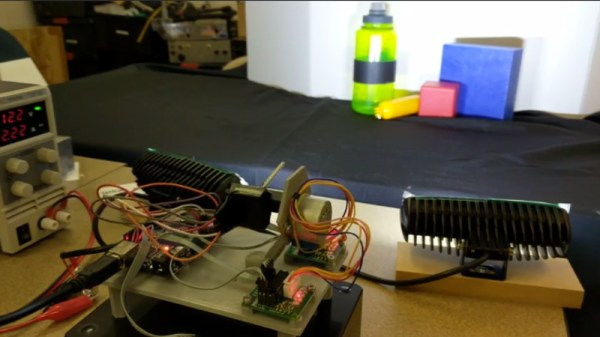

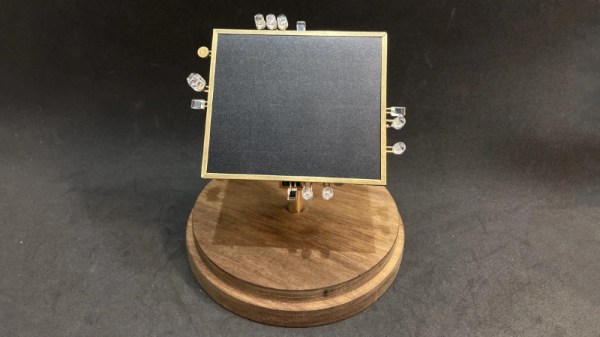

The robot aims to track the brightest source of light it can see. This is achieved by feeding signals from four photodiodes into some analog logic, which then spits out voltages to the two motors that aim the robot, guiding it towards the light. There’s also a sound-detection circuit, which prompts the robot to wiggle when it detects a whistle via an attached microphone.

The robot aims to track the brightest source of light it can see. This is achieved by feeding signals from four photodiodes into some analog logic, which then spits out voltages to the two motors that aim the robot, guiding it towards the light. There’s also a sound-detection circuit, which prompts the robot to wiggle when it detects a whistle via an attached microphone.